DUBAI: Rawan al-Aleku was visiting a friend in Debrassye, north-east Syria, in the summer of 2020 when he was drafted by the Syrian Democratic Forces, a coalition of Kurdish and Arab militias, to fight Daesh in 2014. She was only 16 years old.

Telling al-Aleku’s story, his Iraqi Kurdistan-based relative Farhad Oso, a human rights activist, told Arab News that the schoolgirl was effectively abducted when her friend’s mother took her to the local Kurdish security office. .

Al-Aleku himself was taken to a boot camp for young soldiers, where he conducted months of grueling military drills and political sermons. According to Osso, he had no contact with his family the entire time.

As the weeks turned into months, al-Aleku’s father, Omran, increasingly angrily demanded his release, which resulted in his arrest.

Upon release, he published an open letter on Facebook demanding his daughter’s freedom.

“My case is about kidnapping, kidnapping her home, her school and her friends and her childhood,” Omran wrote in a direct appeal to SDF’s Commander-in-Chief Mazloum Abdi. End the practice of child recruitment.

“These traitors kidnapped my daughter. I’m told you’re following through with your pledge, so why do you apply the rules only where you think it’s appropriate? You have stolen my past, present and future.”

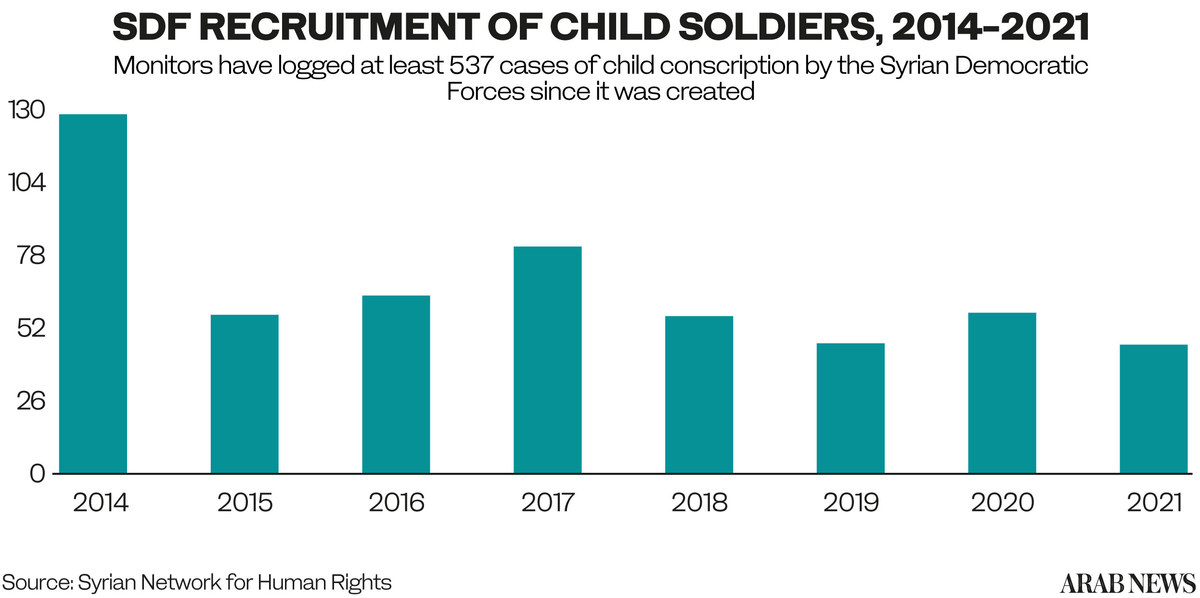

Al-Aleku’s story is not alone in northeastern Syria. When Daesh began to take over the region in the summer of 2014, the SDF formed a multi-ethnic coalition, working closely with a US-led coalition to retake the region from extremists. In the process, many underage fighters were swept into its ranks.

Prior to the Syrian uprising of 2011, the Kurdish language and culture had been suppressed by the regime of President Bashar Assad.

But when regime troops were withdrawn from Syria’s multi-ethnic north to quell rebellions elsewhere, the Kurds began to manage their own affairs.

In 2014, with the rise of Daesh, Kurds rallied to defend their newfound independence.

Syrian Kurds won global acclaim for their sacrifices, which resulted in Daesh’s final regional defeat in the city of Baguz in March 2019.

Women in the ranks of the SDF were a particular source of inspiration, who were later portrayed as horror heroines in films and even video games.

Rojava, the Kurdish-led autonomous region of northeastern Syria, quickly became an epicenter for the broader Kurdish cause, wrapped in the revolutionary socialist fervor of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or neighboring Turkey’s PKK.

Once the threat of Daesh in Syria subsided, many people living in Rojwa began to express reservations about the main force’s political objectives within the SDF: the People’s Protection Units, or YPG.

The YPG is the militia of the Democratic Union Party or PYD, a Syrian-Kurdish nationalist group affiliated with the PKK, which has waged a decades-long guerrilla war against the Turkish state in pursuit of greater political and cultural rights for Kurds. Southeast of the country.

According to a report by the Atlantic Council, Kurds from Turkey, Iran and Iraq have traveled to Syria to join the YPG, to support the PYD’s political and military efforts in Syria.

QuickFact

The recruitment and use of children by armed forces or groups is a serious violation of child rights and international humanitarian law.

Sources told Arab News that while some Syrian Kurds were attracted to the ideals of the PKK, others saw them as foreign and subversive.

As the demand for the SDF’s military increased to prevent terrorist attacks and subsequent Turkish cross-border infiltration – first in Afrin in 2018, then in north-east Syria in 2019 – the SDF’s recruitment quotas were increasing to more and more young fighters. was taken in. Source.

Osso says he and his fellow human rights activists have documented more than 80 similar cases of the SDF forcibly taking minors with them.

Among them was a 15-year-old girl who went missing in December 2021 in the border town of Kobane.

“Her parents received confirmation that she was there, but the Revolutionary Youth Movement refused to give her back,” Oso said, referring to the PKK-affiliated group that hired her.

“Typically, all children kidnapped in northern Syria receive military and combat training and, most importantly and most dangerously, children are subjected to intense brainwashing, where they are forced to forget their parents. and where did they come from,” he added.

“The ideals of the PKK matter. The parents are not allowed to have any contact with their children during the training.”

Analysts say that as the SDF grew in power and influence during the war against Daesh, so did the PKK, which had established its presence in Syria’s northeast around the same time.

Thousands of its fighters moved from the Qandil Mountains in Iraq’s northern Kurdistan region to take advantage of strategic opportunities opening up on the southern edge of their mortal enemy Turkey.

Companions of the mountains were often greeted with open arms, with local groups noting their discipline and battlefield experience.

Posters in Rozwa towns depicting “martyrs” of recent battles were always topped with the collapse of the PKK, while the dead of the SDF and YPG appeared at the bottom. Many of the casualties were not old enough to carry weapons.

The recruitment and use of children by armed groups is considered a serious violation of child rights and international humanitarian law.

In 2019, after facing criticism for the continued recruitment of children by SDF factions, Abdi – himself a Syrian-Kurdish veteran of the PKK – agreed to a UN-monitored pledge from the Rojawa administration to end the practice. Signed.

To enforce this commitment, the SDF established the Office for Protection of Children from Armed Conflict, which is credited with demobilizing and returning more than 200 children to their families.

But in November 2021, dozens of Kurdish families gathered outside the UN compound in the northern Syrian city of Qamishli, accusing the SDF of breaking their pledge.

Responding to the allegations, Farhad Shami, head of the SDF’s media centre, said the reports of ongoing child recruitment are false and exaggerated.

“The SDF does not have any recruits under the age of 18,” he told Arab News. “The advice follows written laws and regulations, which clearly state that no minor is allowed to engage.”

Shami believes that the Revolutionary Youth Movement, an unarmed faction, recruits minors, but only with parental consent.

“We, at the SDF, confirm the implementation of all conditions if anyone wants to join our forces, the most important of which is the appropriate age requirement,” he said.

However, Bassem Alhamd, co-founder and executive director of Syrian for Truth and Justice, told Arab News that “all armed forces of all factions in Syria are to blame” for the recruitment of child soldiers.

“The only difference is that the SDF signed a pledge with the United Nations in 2019 to stop the exercises, unlike Syrian regime forces and rebels,” he said.

“While the children were returned to their parents after that, the incident is not over yet. There should be zero cases of child recruitment. ,

A report prepared by Syrians for Truth and Justice cited at least 17 cases of recruitment of boys and girls during the last three months of 2021, of whom only one returned home. The fate of others remains unknown.

A report by the Syrian Network for Human Rights said that at least 156 fighters as children remain in the SDF ranks, and 19 were recruited in November 2021 alone.

Wherever children have served in war zones, the lasting damage to cognitive development and emotional well-being is well documented.

“It’s a heavy topic to deal with,” Alhamad said. “Unfortunately, children who spent months in training camps are in dire need of psychological support – a service rarely provided at this time.”

When al-Aleku was returned to his family a year later, his character had changed dramatically, remodeled to meet the intense demands of soldiers and the duties of a loyal revolutionary.

“He was brainwashed by the communist ideals of the PKK and was given arms training,” Osso said. “Her parents were distraught.”

,