Syrian refugees under pressure to return fear an uncertain future

DUBAI: When Amir left his war-torn hometown of Homs, western Syria, in 2013, he believed he was going somewhere that would offer him and his family permanent safety and sanctuary from their country’s ravaging civil war. will provide.

Packing what little belongings had survived the regime’s incessant barrel bombardment, Amir boarded a bus to Lebanon with his sister, Alia, and their child, Omar, where the three settled in a camp in Arsal, Baalbek .

“My brother is a proud man,” Alia told Arab News from her adopted home in Lebanon. “After our parents were buried under the rubble, she took it upon herself to look after us and raise my son, Omar.”

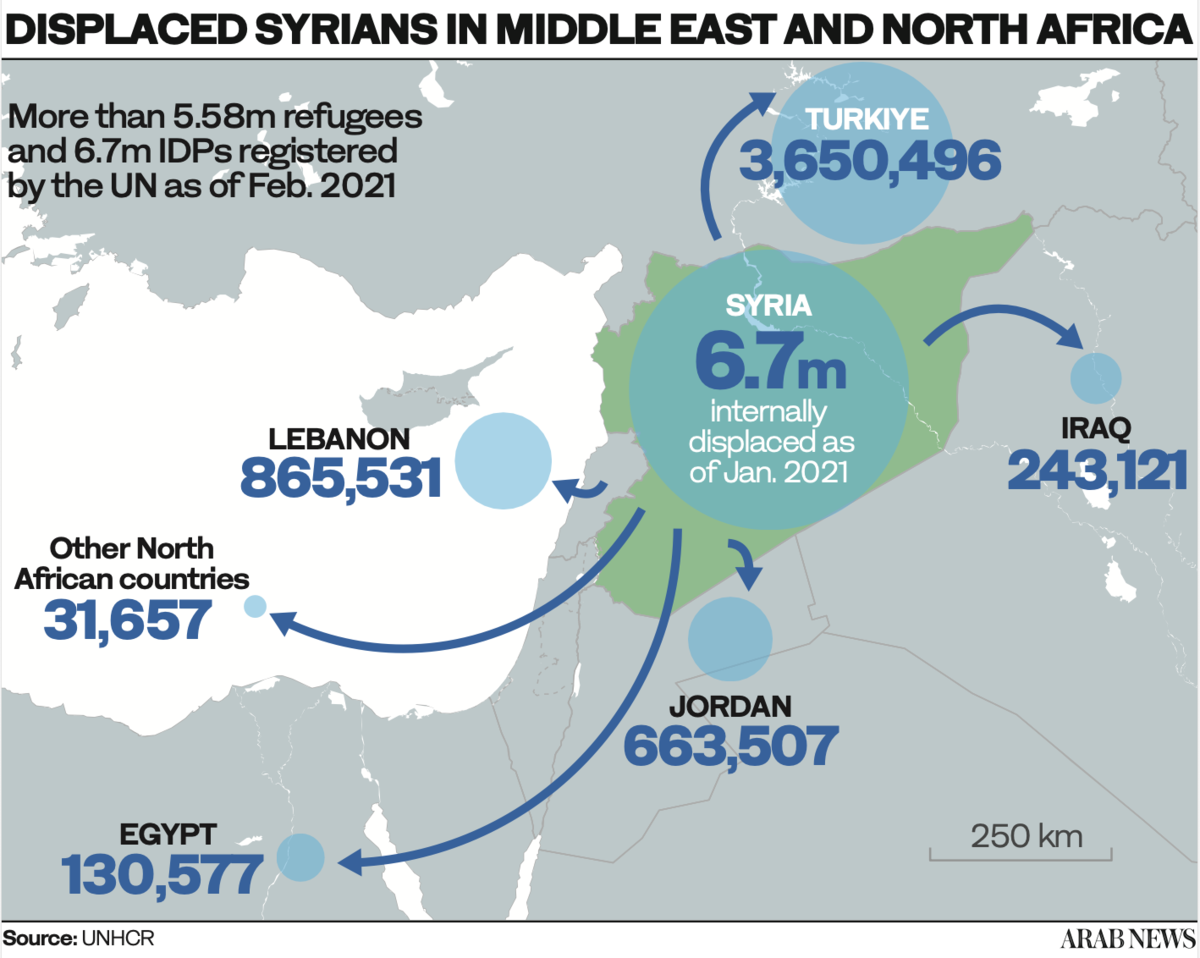

In doing so, Amir and his family joined the ranks of millions of Syrians displaced by the civil war – most of whom have settled in neighboring Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, while others have fled to Europe and beyond.

What began in 2011 as a peaceful protest movement demanding greater civil liberties quickly escalated into one of the world’s bloodiest conflicts, with the death toll now in the hundreds. Is.

About 13 million people have been displaced by the war. (AFP)

Another 100,000 people have gone missing, likely tortured and killed by security service agents in Bashar Assad’s prisons. To date, some 13 million people have been displaced by the war – 5.6 million of whom have fled abroad.

Now, many of the countries that offered sanctuary have drawn up plans to turn back their Syrian guests either voluntarily or by force, despite warnings from aid agencies and refugees themselves that Syria is unsafe and poverty-stricken. .

Syrian refugees are viewed by the Assad regime and its loyalists as traitors and dissidents. Human rights observers have identified cases of returnees being harassed, detained without charge, tortured and even disappeared.

Nevertheless, countries such as Lebanon, Turkey and Denmark, grappling with their own economic pressures and rising anti-immigrant sentiment, are pushing for Syrians to return home, claiming that the civil war is now over.

In 2021, Denmark adopted a “zero asylum-seeker” policy, as a result of which many Syrians who had been based there since 2015 had their residency status revoked, while others were removed from deportation facilities.

Struggling to care for its native population, Lebanon’s crisis-hit caretaker government announced its own repatriation plan in October this year, which aims to send back 15,000 refugees per month.

According to reports, the situation in Turkey is no different. Stories have emerged on social media of refugees being forced to sign voluntary return forms.

According to reports from the France-based advocacy group Syrians for Truth and Justice, Syrians released by Turkish authorities at the Bab al-Salamah border crossing are classified as “voluntary returnees” despite it being a regime-controlled crossing.

Those who return, voluntarily or otherwise, often face harassment, extortion, forced recruitment, torture and arbitrary arrest, regardless of their age or gender.

Mazen Hamada, a high-profile activist and torture survivor who has testified about the horrors of the Syrian regime’s prisons, shocked the world when she decided to return to Damascus in 2020.

Hamada, who has long spoken of his mental anguish and loneliness in exile after his release, was returned to Syria from the Netherlands under an amnesty agreement that reportedly guaranteed his freedom.

However, upon his arrival in Damascus in February 2020, Hamada was arrested and has not been seen or heard from since.

Last year, human rights monitor Amnesty International released a report titled “You Are Returning to Your Death”, which documented serious violations committed by regime intelligence officers against 66 returnees, 13 of whom were children. Were.

Some 100,000 people have disappeared in Bashar Assad’s prisons, likely been kidnapped and tortured and killed by security service agents. (AFP)

Five of the returnees died in custody, while the fate of 17 is unknown. Fourteen cases of sexual assault were also registered – seven of which involved rape – against five women, a teenage boy and a five-year-old girl.

Another Istanbul-based advocacy group, Voice for Displaced Syrians, published a study in February this year titled, “Is Syria Safe to Return? Perspectives of Returnees,” 300 returnees and four governorates in the interior Based on interviews with physically displaced persons.

Their accounts outlined extreme human rights violations, physical and psychological abuse, and a lack of legal protection. Some 41 percent of respondents had returned to Syria voluntarily, while 42 percent said they had left out of necessity as a result of poor living conditions in their host country and a longing to reunite with family.

With regard to their treatment upon arrival, 17 percent reported that they or a loved one had been arrested arbitrarily, 11 percent reported harassment and physical violence inflicted on them or a family member, and 7 percent did not respond. decided to.

For internally displaced persons, 46 percent reported that they or a relative had been arrested, 30 percent reported physical harm, and 27 percent said they faced persecution because of their origin and hometown. Had to do Many also reported difficulties in retrieving personal property.

With regard to their treatment upon arrival, 17 percent reported that they or a loved one had been arrested arbitrarily, 11 percent said they or a family member had been subjected to harassment and physical violence. (AFP)

Despite a growing body of evidence suggesting that the regime continues to target civilians it considers dissidents, many countries are choosing to pursue normalization with Assad, lobbying for his resettlement in Arab and reopening our embassies in Damascus.

For the relatives of the returnees who have gone missing, these developments smack of betrayal.

Amir, who eventually returned to Syria voluntarily, appears to have suffered the same fate as activist Hamada. Tired of living in poverty in Lebanon, away from his extended family, he moves back in October 2021. Since then there is no news of him.

“Life in Lebanon has become rather unbearable. Amir used to return humiliated every time he left home,” his sister Aaliya told Arab News.

Initially living in a tent provided by the UNHCR in Arsal, Amir and his family eventually managed to acquire a small one-bedroom house near the camps. Alia said it was a constant struggle to scrape together enough money to pay the rent.

Most refugees are unable to secure steady employment due to their lack of official papers, which under normal circumstances would provide them with residence and a steady income. Amir, like many working-age men around him, resorted to hard physical labor.

Those who try to find work in the larger cities risk being arrested at Lebanese checkpoints, imprisoned, and deported for being in the country illegally.

Since Aamir’s disappearance, Alia has been forced to work on a single income cleaning houses.

What began in 2011 as a peaceful protest movement demanding greater civil liberties turned into a brutal crackdown by the Bashar Assad regime, and one of the world’s bloodiest conflicts. (AFP)

Aaliya said, “He couldn’t take it anymore, being talked to like a little boy by some of his employers and hearing derogatory comments.”

“It happens to me too, but I hold my tongue. I can’t afford to stand up for myself. He thought he would take advantage of his opportunities and return to Syria to acquaint us back in the hope of finding a place.

She says she begged her brother to leave, aware of several refugees she knew personally who had been mistreated upon their return to Syria. Some were held in jail pending bail, while others had gone missing.

“But he didn’t listen,” said Alia. “He’s been gone for over a year and I haven’t heard from him.”