Dubai: Libya occupies a sensitive position in the security of Arab and European countries and in managing migration flows to the Mediterranean region. Yet a road map for the restoration of the oil-rich nation’s security and stability is far from the international community.

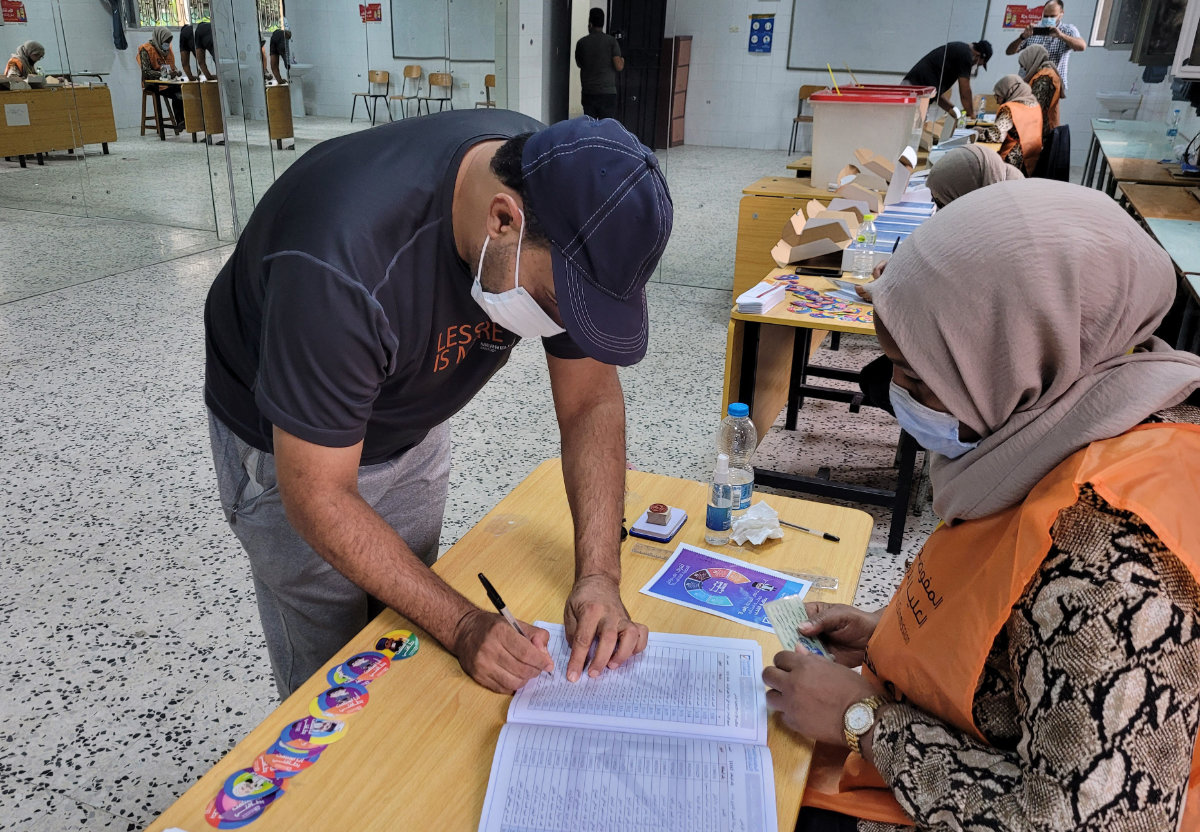

Libya’s first presidential election since the overthrow of dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 was due on 24 December, amid hopes of eventually uniting the war-torn North African country after years of bitter turmoil.

However, just two days before the United Nations-sponsored election opened, voting was postponed amid electoral hurdles and an ongoing legal wrangling over election rules and who is allowed to stand.

Libya’s electoral board called for the election to be postponed for a month until January 24, when the parliamentary committee to oversee the process said it would be “impossible” to hold the vote originally scheduled.

Even now, 10 days into the new year, it is unclear whether the election will go ahead. Many fear that the delicate peace in the country could be disturbed if the disputes over the elections are not resolved quickly.

Any delay will result in a major setback to the international community’s hopes of reunification of the country.

“This is a critical moment for Libya and the signs are increasing day by day that we are running out of time for free and fair elections,” said Ben Fishman, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Arab News.

“Several court cases against leading candidates have curtailed the campaign season. All this shows that these elections are not going on the agreed constitutional basis. More time is needed to resolve the fundamental issues, not only on who can run, but also what the powers of the President will be. ,

Without an agreement relating to those powers, Fishman said, the election resulted in “a growing recipe for more polarization, as well as a growing potential for more violence and no less.”

One particularly controversial candidate to emerge before the vote is Saif al-Islam Qaddafi, son of Muammar Qaddafi and a strong presidential contender.

On 24 November, a court disqualified him to run. His appeal against the verdict was delayed for several days when armed militias blocked the court. On 2 December, the verdict was overturned, clearing the way for his stand.

A Tripoli court sentenced Qaddafi to death in 2015 for war crimes committed during the war to prolong his father’s 40-year rule in the face of a NATO-backed insurgency in 2011. However, he was granted a pardon and released the following year by the United Nations-backed government. He remains a key figure for Libyans loyal to his father’s government.

Gaddafi is not the only divisive candidate. Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, who temporarily suspended his command of the Libyan National Army based in Tobruk to run for office in September, also faces legal proceedings for alleged war crimes.

According to Jonathan Viner, a scholar at the Middle East Institute and a former US special envoy for Libya, the chances of success for the election were severely diminished from the start when the Libyan House of Representatives drafted the rules.

“These elections have become increasingly chaotic,” he said. “The process of who gets disqualified and who doesn’t is, at least, somewhat flawed, incomplete, and with so many candidates the idea that nobody will get a majority – nobody will get a majority.”

Given the ongoing controversies, Dalia Al-Aqeedi, a senior fellow at the Center for Security Policy, believes January 24 is too ambitious for a rescheduled vote.

“Despite all the continued calls for the importance of holding a Libyan presidential election, crossing the country to safety and helping prevent a new wave of violence, this is likely to happen due to a lack of agreement between the major key players.” The chances are slim, divisions on the ground, and foreign interference,” Al-Aqeedi said.

“Conducting elections in January is a difficult task as any impediment to the postponement of the electoral process was neither addressed or dealt with by local leaders nor by the international community.

“Less than a month is not enough to resolve all the issues that prevent Libyans from casting their votes, and this includes the struggle over the nomination of candidates.”

QuickFact

The factions disagree on basic electoral rules and who can run for office.

The parliamentary committee said it would be “impossible” to hold the vote as scheduled.

Al-Aqeedi is concerned that factional fighting could resume if foreign interference continues. “The potential for violence and anarchy is very high, especially due to the increase in the efforts of the Muslim Brotherhood in the country due to its damage everywhere in the region,” she said.

“The group, which is backed by Turkey, is looking at Libya as an alternative to Tunisia, which was its last stronghold.”

Fishman of the Washington Institute also doubts elections will be held later this month, but remains cautiously optimistic that a serious escalation in violence can be avoided if talks continue.

“It now appears that the immediate threat of violence is low as various actors are talking about next steps,” he said. “Due to these talks, the date is likely to be pushed to the end of January or even several months later.

“The international community should support these internal Libyan talks and UN-brokered talks and not take a specific position on election time until a better consensus is more clear.”

The appointment of Stephanie Williams as the UN Special Adviser on Libya on December 7 offers some hope of getting the process back on track. Williams led the negotiations that resulted in a ceasefire in Libya in October 2020.

Fishman said, “She is deeply entrenched in issues and knows all parties, and hopes that she can pull a rabbit out of a hat and do what her predecessor was not able to do and play a game.” Came up with a plan and a timeline.”

The road to the presidential election in Libya was never going to be easy. In August 2012, following the fall of Muammar Qaddafi, the rebel-led National Transitional Council handed power to an authority known as the General National Congress, which was given an 18-month mandate to establish a democratic constitution.

However, instability remained, including a series of major terrorist attacks targeting foreign diplomatic missions. In September 2012, US Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans were killed in an attack on the US consulate in the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi.

Responding to the threat, Haftar launched an offensive against armed groups in Benghazi in May 2014. He named his army the Libyan National Army.

Elections were held in June 2014, resulting in an eastern-based parliament, the House of Representatives, dominated by anti-Islamists. In August of that year, however, the Islamic militia responded by invading Tripoli and restoring the GNC to power.

The House of Representatives affiliated with Haftar took refuge in the city of Tobruk. As a result, Libya was divided, left with two governments and two parliaments.

In December 2015, after months of negotiations and international pressure, rival parliaments signed an agreement establishing a nationalist government in Morocco. In March 2016, GNA chief Fayez al-Sarraj arrived in Tripoli to set up a new administration. However, the House of Representatives did not hold a vote of confidence in the new government, and Haftar refused to recognize it.

In January 2019, Haftar launched an offensive in oil-rich southern Libya, capturing the region’s capital, Assembly and one of the country’s main oil fields. In April of the same year he ordered his army to advance on Tripoli.

However, by the summer, when Turkey deployed troops to protect the administration in Tripoli, the two sides had reached a standoff.

A UN-mediated ceasefire was agreed in Geneva on 23 October 2020. This was followed by an agreement to hold elections in Tunis in December 2021.

A Provisional Government of National Unity, headed by Abdul Hamid Dabibah, was approved by parliamentarians on March 10, 2021. However, on 9 September, the Speaker of the Libyan Parliament, Aguila Saleh, ratified a law governing presidential elections, which was seen to be bypassed. In favor of due process and the week.

Subsequently, Parliament passed a no-confidence motion in the Unity Government, putting the elections and hard-won peace in doubt.

Even if elections are held in January, Libya still has a long way to go to form a stable administration and achieve a lasting peace.

,

, Twitter: @rebeccaproctor

,