K Satchidanandan(75) fondly remembers that moment in 1972 when a poem of his, The blind man who discovered the sun, appeared in the Sahitya Akademi’s bi-monthly journal, Indian Literature. He was a 26-year-old poet living in Kerala and writing primarily in Malayalam, and to be published by the Sahitya Akademi in New Delhi was a recognition at a national level he had been striving for. “Sahitya Akademi held a place of pride in the world of Indian literature. There was no comparable institution at that time,” said Satchidanandan. “Every Indian writer wanted to be connected to it in some way or the other.”

Two decades later, Satchidanandan got the opportunity to be the editor of the same journal. By then he was a leading modernist poet in Malayalam. He had also been a professor of English Literature at Christ College in Irinjalakuda for the last 25 years. The choice to move to Delhi, leaving behind the life and fame in Kerala, was a fearful one, he recounted. But then the prestige of being associated with the Sahitya Akademi, and editing a journal with such a wide readership, was alluring enough for Satchidanandan to take up voluntary retirement from his job and move to a life of what he calls ‘near anonymity’ in Delhi . “You would be surprised to know that the salary offered by the Sahitya Akademi then was less than that I was being paid by the college,” he said laughing. “But still this was an opportunity I was not willing to give up.”

The Akademi was at that time already close to 40 years old. It was conceived of by the first education minister of the country, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, with the objective of providing a national platform to writers like Satchidanandan, who would otherwise have been known only in the language circles in which they wrote. In order to establish the institution, a Conference of Letters was convened on March 15, 1951, attended by representatives from 19 state governments and numerous literary organisations. In his address to the conference, Azad explained that in India, there was a long tradition of state patronage of men of letters, which had been missing during colonial rule. The time had come to revive this tradition, and for that, he proposed the creation of an Indian Academy of Letters, “which will coordinate literary activities in all Indian languages”.

The name of the Academy was not an easy one to decide on, given the many shades of language politics afflicting the newborn Indian nation at the time. Historian Riswan Qaiser in his book, Resisting colonialism and communal politics: Maulana Azad and the making of the Indian nation (2011), noted how the first name proposed by the committee appointed for the establishment of the academy was ‘Bharat Bharati’. The Madras government clearly expressed its disapproval of the name and stated their preference for the name ‘Indian National Academy of Letters’. Two other names, ‘Sahitya Bharati’ and ‘Sahitya Niketan’, were also suggested, but finally, a consensus was met upon ‘Sahitya Akademi’, which would be the closest translation of the ‘Academy of Letters’.

Once the name was decided, a resolution was passed detailing the objective of the Akademi to “foster and coordinate literary activities in all the Indian languages and to promote through them all the cultural unity of the country”. The name of Jawaharlal Nehru was proposed as its first president, who held the role till his demise in 1964. Qaiser in his book noted that “before sending a note to the office of the president, for appointing Pandit Nehru as the first chairman of the Akademi, the Ministry of Education had made it clear to the prime minister’s secretariat that his nomination was not on account of his being the prime minister but in his personal capacity as a ‘man of letters’.”

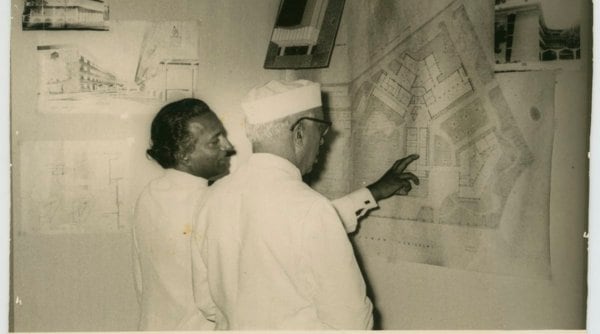

Thereafter, the Sahitya Akademi was inaugurated on March 12, 1954, in the Central Hall of the Parliament. For the first few years of its existence, the Sahitya Akademi was located in the Theater Communications Building in Connaught Place, where Palika Bazar exists today. In 1961, it was shifted to Rabindra Bhawan in Mandi House, which was built to mark the birth centenary of the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore. Apart from the Sahitya Akademi, the Lalit Kala Akademi and the Sangeet Natak Akademi were also shifted into this new building designed by architect Habib Rahman.

Rahman’s son and renowned photographer Ram Rahman recollected how involved Nehru was in the making of the building. He remembered how his father was rebuked by the then prime minister for coming up with an initial design for the building which looked like an ordinary office. “My father then reworked the whole idea. He used local Delhi stones and made architectural interventions that were inspired by the Tughlaq buildings in Delhi. He also used jaali a lot, both as a see through and as a surface,” explained Rahman. Rabindra Bhawan in that sense was the first institutional building in Delhi, in which the architect combined modernist styles of architecture with Indian sensibilities.

When Satchidanandan made Rabindra Bhawan his literary home in 1992, he was pleasantly surprised to be introduced to literature in languages that he had hardly encountered in his life. “That is the major mission of the Akademi – to bring together writers from different languages and have a common platform for them to talk to each other and discuss specific issues concerning their languages,” he said. He was particularly impressed to discover the rich repository of literature in the Northeastern languages. “It redefined my idea of Indian culture and civilisation,” he said.

From 1996, when Satchidanandan became the secretary of the Akademi, he tried to open it up to more young writers. “Until then the Akademi was mostly a club of the old elite,” he said.

Despite the many ways in which the Sahitya Akademi has tried to give a uniform platform to languages from across the subcontinent, it is also a ‘quintessentially Delhi institution’, noted cultural anthropologist Rashmi Sadana. “Delhi as the national capital represented the Nehruvian ideology of unity in diversity. Yet it sometimes struggles to translate this unified idea of India into the everyday life, politics and cultural practices of the city. That struggle is mirrored by the Sahitya Akademi as well,” said Sadana. “The Sahitya Akademi negotiates the many languages it represents in Hindi and English, much the same way in which people in Delhi bridge the many different linguistic groups in the city through these two languages.”

Sadana also explained that the real contribution of the Sahitya Akademi lies in the recognition and support it has given to smaller languages. However, its impact on the cultural life of Delhi has remained limited. “It did not have the kind of excitement as is often associated with institutions like the India Habitat Center or the National School of Drama,” she said.

Satchidanandan explained the lack of mass popularity of the institution by suggesting that “literature, by its nature, can never be as popular as the performing arts, which have a more direct appeal among the viewers.”

At present the Sahitya Akademi recognizes 24 languages. “But the Akademi is for all the languages,” said K Sreenivasarao, the current secretary. “There are close to 700 or 800 languages in India. We make it a point to give recognition to four different languages among them every year.”

,