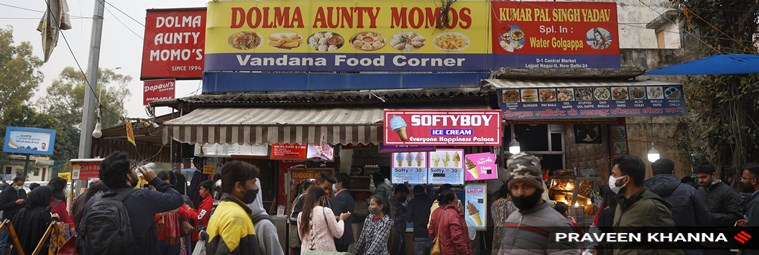

Get in line! Distance banake rakhiye (Keep some distance)” is reminiscent of Dolma Tsering, a school teacher desperately trying to discipline an unruly group of students. Except, everyone standing in front of her is adults—something masked, less Heeding caution. They all seem to be galloping towards Tsering’s shop in Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar, weaving through the crowd to reach a plate of piping-hot momos,

for nothing reduces the country’s hunger momosNot even a major pandemic. food aggregator zomato Recently posted a report on his Instagram feed titled “Presenting the 2021 Meme Rewind and a Little Bit About How India Ordered”, which claimed that Momo has given some to Vada Pav and its long-standing rival Samosa. Won over a million orders. It got more than 1 crore orders like biryani Consolidated its top position with two biryanis every second.

As COVID-19 cases rise againDelhi’s food vendors, mostly migrants, are vulnerable to the lockdown and fears of loss of livelihood. ,Bohot mushkil ho jayega agar lockdown ho gaya phir se (It will be difficult to survive another lockdown),” says 53-year-old Tsering. Not listed with a food aggregator, the lockdown meant zero revenue for him in the long run. Tsering named its takeaway spots after customers – “dolma aunty”, an adjective reserved for women of a certain age, and dolma aunty momos became somewhat of a landmark in one of Delhi’s busiest markets. since it started running shoppers with steamed. Dumplings in 1994.

At the time, she and her sister-in-law would go to the market every evening, carrying a plastic stool that served as a stand for their steamer pot and a kilo or two of folded, uncooked momos they expected. That would sell. At the end of the day. Twenty eight years later, four Dolma Auntie Momos outlets stand proudly in the city. “It was difficult in the beginning,” says Tsering, who had never negotiated the streets as a salesperson before. She came to the capital in 1990 as a new bride, and was employed as a domestic worker. “I did many jobs – cleaning, washing, cooking, even as a runner for people – but could not fill my stomach. That’s when my sister-in-law and I decided to start our own momo business,” she says.

Steamed momos revolutionized the fried image of street food. (source: Getty Images)

Delhi that was once connected fried food Along the streets, his efforts did not take pity. They used to accuse her boiled momos of being raw, making them sick. She hardly tried to explain in broken Hindi what momos are. “But those who bought our momos kept coming back. And with that, we were able to make enough money to feed ourselves,” she says.

It is unknown when Momo arrived in the country. Estimates suggest that this was when Dalai Lama He sought asylum in India in 1959. Thousands of Tibetans, including Tsering’s parents, followed their leader. Momo came with him. “Ten or fifteen small meat dumplings (mo-mo)” are often the lunch of a Tibetan gentleman, noted Tibetologist and British India’s ambassador to Tibet, Charles Alfred Bell, in his book People of Tibet (1928). But here, it remained confined to Tibetan settlements which were settled across the country – Majnu ka Tila (Delhi), Bylakuppe and Mundgod (Karnataka), Puruwala (Himachal Pradesh), Tezu (Arunachal Pradesh), among others. Since most settlements functioned largely as self-sustaining units, with daily activity and interaction confined to the community, momo was also made and sold primarily by Tibetan refugees, except for a few momoficionados, who made special trips to it. did it

Nepalis also contributed to its spread. It is said to have been picked up by the Newar merchants of Kathmandu during their travels along the Silk Route. Method, is traditionally made with yak meat in Tibet, and brought to India. Many momo sellers trace their ancestry to the Gorkha community (the British army began recruiting Nepalis as “Gorkhas” in 1815), and refer to Sikkim as their home, where momos have traditionally practiced their ancestry. Honton – a cheese-stuffed steamed dumpling with millet flour – as the state’s favorite dish.

Momos are essentially parcels of myriad types of fillings, and find an expression in most cultures. It is Gyoza of Japan, Jiaozi of China, Mandu of Korea, Manti of Turkey, Mantu of Afghanistan. Poland’s pierogi and Italy’s ravioli or agnolotti can also be compared. In India too, steamed savory or sweet variants existed before momos. Gujiya, a farsa from Varanasi, dumplings filled with jaggery-coconut, like those from Maharashtra modak, Bhapa Puli Pithe of Bengal, Kozhukattai of Kerala, Kolukattai of Tamil Nadu or Kudumulu of Andhra Pradesh.

Outside the Himalayan region, Momo, as we know it today, remained relatively unknown to the rest of India until the 1990s. When a new liberal economy promised jobs and better living conditions, it moved migrants, especially from the Northeast, to metro cities like Delhi. Immigrants, Nepalese and Lhotshampas, Bhutanese of Nepalese origin who had been made refugees in their own country, also arrived in India. came with them Recipes, Despite liberal attitudes towards them, most refugees and migrants have struggled with invisibility, social exclusion and the denial of their rights. This prompted many migrants, especially women, to rely on the strength of their culinary skills to gain a foothold in the city.

Entrepreneurs like Tsering are dominating the country today, selling momos in the evening and going to the margins. “It’s so easy now; when we started, ladies-log itna bahar kaam nahi karte thhe (Women did not go out to work much). We would feel awkward as the only female seller in the market,” she says.

Ubiquitous in most cities, it is sold outside metro stations, bus stands, schools, colleges and offices, even near hospitals. “I have often seen people selling momos on bicycles. They hang uncooked momos on its handle and put a steamer on the carrier. And it is sometimes their entire shop, the anatomy of the bicycle acting as the basic structure of their shop,” says Shamita Choudhary, architect and founder of Malba Project, a construction/demolition project. waste management Start-up, which frequents the Momo sellers in the neighborhood of its office.

At dawn, in the “urban village” of Chirag Delhi, migrant workers begin chopping onions, garlic and ginger, rolling out small maida balls, and stuffing them with cabbage and carrot or chicken fillings. Each dumpling is shaped like a crescent moon or a thick, round bundle. These are supplied by noon to momo vendors, who sell them across the city. In wholesale markets like Sadar Bazar, readymade and frozen momos are also sold by the kilo.

Vendors, like this relatively invisible workforce, also come from elsewhere. Pradeep Ghorai, 32, from Medinipur in West Bengal, who sells momos from a “Chinese van” in New Rajendra Nagar, first tasted it in 2001 in Delhi’s Munirka. “I came here looking for work and someone bought me a plate. I didn’t like the taste of it initially,” he says. Then, why does he sell it? “Because it sells,” he says. it is said.

For Izasil Kane, 36, unlike Ghorai, it’s a way of remembering her life in Dimapur, Nagaland, where she once ran “a small restaurant”, which she managed after saving enough money from her Delhi job. Hoping to be alive again. global pandemic was difficult. She lost a job in a “Korean company” in Greater Noida in 2019. She could neither return home nor did she know what to do next. Then, Momos came to her rescue. “Momos were usually a Sunday affair for us. After the church service my family would gather and make momos for the evening,” she says. In her Zeliang tribe, it “has always been a part of the table” and she “feels close to home” when cooking at the Ministry of Pork in Delhi’s Humayunpur, an urban village next to the upscale Safdarjung Enclave, Where do cafes go? by the people of the Northeast and other states.

Shyam Thakur, 38, founder and CEO of Malaysian restaurant chain Momo King, which he brought to Delhi in 2017 and now has a rapidly expanding cloud kitchen, finds the uniformity in taste of momos served across the city a bit delectable. His venture differentiates Darjeeling momos from Ladakh momos by using Nepali spices like East And wood, They also offer gluten free and vegetarian options. “Momo’s popularity is undeniable. Unique in its versatility, it can be changed to suit any palate without destroying its essence. It is loved by children as well as the elderly, the health conscious and gastronomes add to its popularity,” he says. Momo King plans to expand to Tier-II and -III cities, US and UAE, and aims to open 100 cloud kitchens by 2023.

Their menu also includes the city-bred cult: the tandoori momo. Momo has evolved, and how. from traditional Nepali bags Momos (Momos in a Comforting Broth), For Fusion Creamy Momos, crunchy Momo, Bizarre Momo Pizza or moberg (Momo Burger), and the extravagant chocolate momo at the cloud-kitchen chain, Wow! Momo. “My best friend and I have an annual tradition of eating butter chicken momos – momos in butter chicken gravy. Now that I am a vegetarian, they make my version of paneer. It’s gimmicky but fun. But nothing is as satisfying as the original steamed momos,” says Choudhary.

Behind the adaptable momos, a sign of a developed country, are diaspora like Tsering, who have shaped how India eats food from the edge of the world. “When I started out, I wanted to make enough money to feed my family, but today, momos are embedded in my identity. If you took them away from me, I don’t know who I would be,” Tsering says.

(Damini Raleigh is a food writer from Delhi)

,