Dubai: She is the Arab world’s biggest living music icon, but Fairoz remains an enigma. She maintains a sometimes infuriating aura of mystery, rarely giving interviews and guarding her family’s privacy. On stage she appears devoid of emotion – motionless and expressionless. Those features have become iconic in themselves, with Fayrouz’s striking but emotionless features adorning everything from handbags and posters to Beirut’s city walls.

Born in 1934, Nouhad Haddad has recorded hundreds of songs, starred in dozens of musicals and films, and toured the world during his career. Since 1957, when she first performed at the Baalbek International Festival, she has become one of the Arab world’s best-loved singers. And in doing so, she will unite her often fragmented homeland.

All Lebanese remember the first time they heard Fairoz. For Tania Saleh, it was during her drive to Syria to avoid the start of the Lebanese Civil War. He remembers one song in particular – “Raudani ila biladi” (Take me back to my homeland).

“That song really marked me,” says singer-songwriter and visual artist Saleh. “My mother was crying while she was driving and the song really made it a very emotional moment. And I remember thinking, ‘How can one song affect someone so much? It is just a song. But it also affected me in a way that I did not understand then.

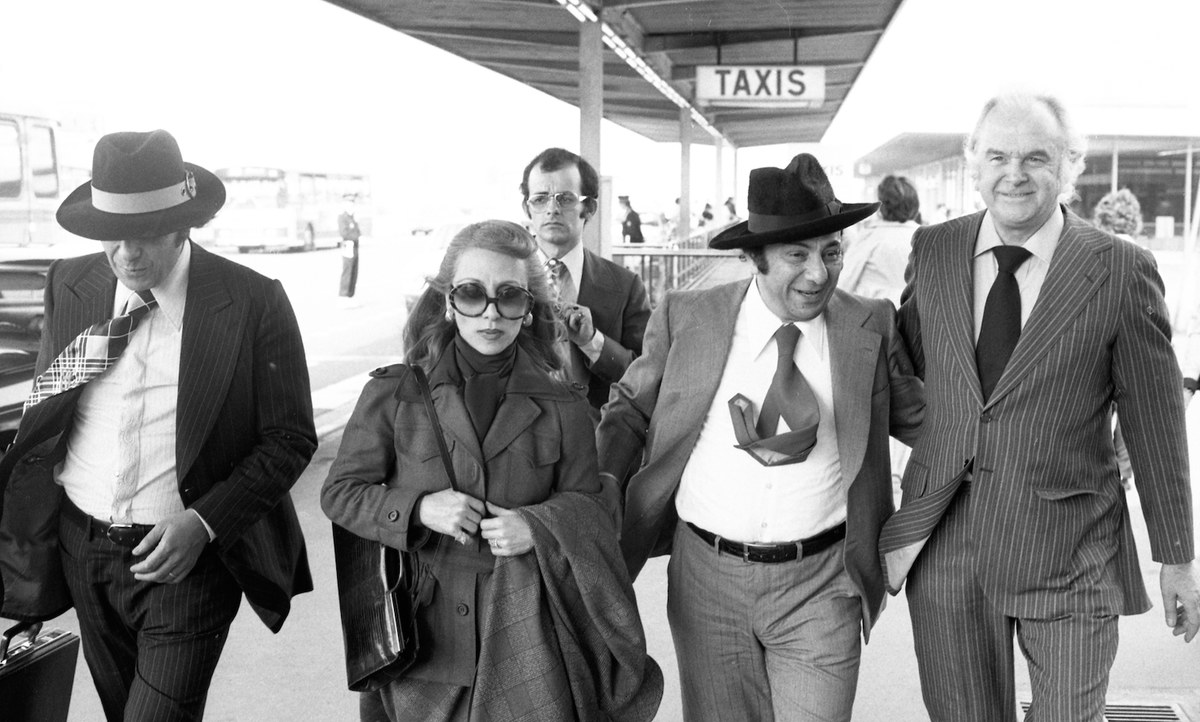

Fairoz (C) with William Haswani (R) and his son Ziad Rahbani (L) dressed as Ottoman policemen in the musical play Mas el-Rim, written by the Rahbani Brothers, at Beirut’s Piccadilly Theater in 1975. (AFP)

Farrow remained in Lebanon for the entirety of the war and refused to take sides. Although she continued to sing in venues around the world, she did not perform in Lebanon until after the conflict was over. This neutrality, and the patriotic nature of many of her songs, meant that she was a rare symbol of national unity, with all sides listening to her music during the 15-year civil war. He was, as Saleh says, “an emotional anchor for all Lebanese during the war,” regardless of religion or political beliefs. When he released “Le Beirut” (arranged and adapted by his son Ziyad Rahbani) in 1984, Fayrouz and Beirut became inseparable. More than ever, he embodied the essence of what it means to be Lebanese.

None of which would have been possible without the music of the Rahbani Brothers. Fairoz, who was a chorus singer at Radio Lebanon in the early 1950s, met Mansour and Assi Rahbani in 1951 through composer Halim al-Roumi. He married Assi a few years later, and together the three revolutionized popular Lebanese music. The Rahbani Brothers combined musical styles including Levantine folkloric traditions and music from Latin America, and incorporated both Western and Russian elements into their compositions. However, it was Farrows who gave voice to his musical vision.

Fairoz sang an almost legendary Lebanese song. She sang of love and desire, but also of an ideal Lebanese mountain village, of olive groves and jasmine, of vineyards and rivers. “Lyrically, they created the Lebanon we love now,” says Saleh, of the brothers who followed in the footsteps of writers such as Khalil Gibran and Mikhail Naimi, who helped create a romanticized image of the Lebanon many of its citizens still live in. are also attached to it. today.

As Palestinian poet and film director Hind Shoufani wrote, Fayrouz “represents the village girl, stories of love, fetching fresh water, mountains, resistance, people’s power; That kind of simple, beautiful daily existence that is in harmony with nature. As such, there is an added, heart-wrenching poignancy to her lyrics, as the Lebanon she sings about bears no resemblance to the Lebanon of today. She sings about a vanishing dream – one that is shared by much of the Arab world.

Fairoz and her husband Assi Rahbani (second from right) arrive at Orly airport in France in 1975 and are met by French impresario Johnny Stark (right). (Getty)

This vision was rooted in Lebanon’s Golden Age, closely linked to the formation of a national cultural identity by Fayrouz in the years following independence from France. As acclaimed indie-music producer Zaid Hamdan puts it, Fairoz will carry that identity “with elegance and depth like no other singer.”

Fairoz and the Rahbani Brothers changed popular Arabic music forever. Umm Kulthoum, another icon of the Arab world, sang songs of love that could last up to an hour and were deeply embedded in the Taarab tradition. Although the songs of Fairuz and the Rahbani Brothers were much shorter, they used the Lebanese dialect and adopted new melodic forms.

“As a musician, I’m very inspired by the dialect that Feroz sings,” says Hamdan, arguably best known as one half of the trip-hop duo Soapkills. – Assi to Ziyad – very cleverly used the Lebanese dialect in his repertoire.

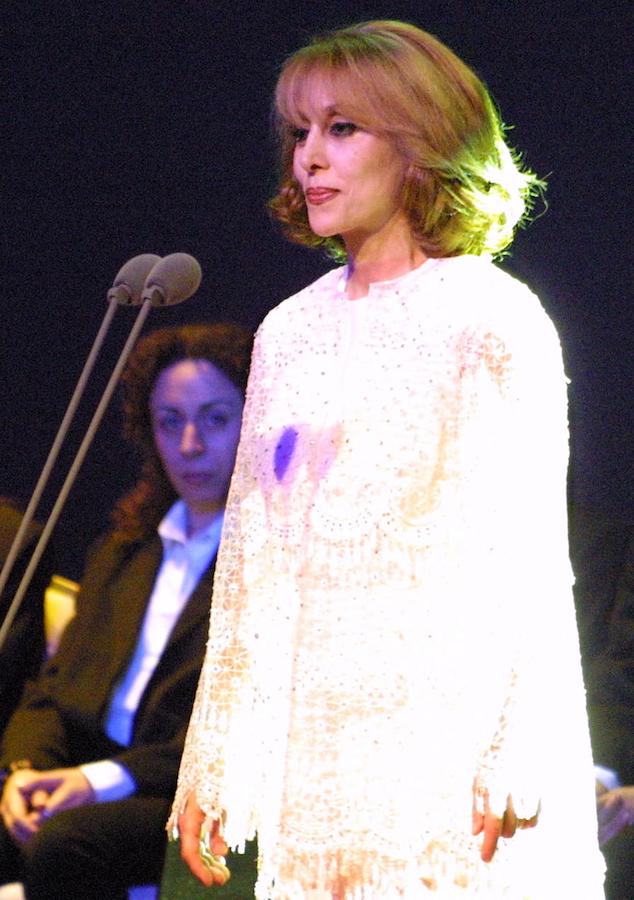

Fairoz performing at the Ice Skating Arena in Kuwait, late May 03, 2001. (AFP)

Hamdan was introduced to Fairuz in the late 1990s by Yasmin Hamdan (no relation), his Soapkills partner. Encouraged by her, he bought a double K7 cassette of Fairoz’s “Andalusiat” and immediately fell in love with the three tracks, one of which was “Yeh Mana Hawa”.

“The lyrics are just incredible,” he says. “It is a form of poetry that is several hundred years old called Muwashash and I wish I could do justice to the beauty of the words.” Another was “Yara el Jadayel”, on which, at a certain point, Farrowz “sings at a very high pitch and very softly, the melody almost whispering over a piano arpeggio”.

It is the wonder and versatility of Feroz’s voice that captivates audiences around the world. Al-Roumi thought her voice was so beautiful that he nicknamed her Firuz (Arabic for Faroese) and became the first person to compose for her.

“Fairoz has one of the most distinctive voices in the Arab world,” says Natacha Atlas, an Egyptian-Belgian singer who has worked with artists such as Peter Gabriel and Nitin Sawhney. “One can always tell that it is (her) voice. It is as delicate as it is beautiful and strong, and the ability of her voice to (carry) such strong emotion is always extraordinary. He is one of my biggest influences. When I listen to him, I often burst into tears at the beauty of his voice and how it evokes a deep nostalgia in me for the Middle East as it once was, and how everything has changed almost beyond recognition.

The pharaoh’s fame outside the Levant can also be traced to his support of the Palestinian cause. In early 1957, Fairuz and the Rahbani Brothers released “Rajiyon” (We Will Return), a collection of pro-Palestinian songs. This was followed by the release of “Al-Quds Fil Baal” (Jerusalem in My Heart) in 1967, and as recently as 2018 she was still dedicating songs to Palestinians killed at Gaza’s border with Israel.

When her husband’s health began to fail in the 1970s, Fairoz began working closely with Ziyad, the eldest of their four children. One of the albums he composed and arranged was “Wahdan”, which was released in 1979 on the Zida record label and includes the song “El bosta”.

“I cherish and love her experience with Ziyad,” says Saleh. “The albums he did with it took him to jazz and bossa nova and sometimes to funk. This gave another dimension to Farrowz – a risk taker. She stepped out of her comfort zone, and that happens very rarely.

This helped solidify her reputation with a younger generation and she continues to evoke a deep sense of nostalgia not only among the Lebanese, but throughout the Levant and North Africa. Many Lebanese still start their day listening to Fairuz’s songs and he is revered as a cultural icon, despite family disputes over royalties, his controversial performance in Damascus in 2008, and allegations of plagiarism against the Rahbani family. Status quo. When French President Emmanuel Macron visited Lebanon in 2020, he chose the home of the Faroes as one of his first ports of call, not the country’s political leaders.

“He described this beautiful Lebanon and he made us dream that it was our country, which was actually a picture he made,” says Saleh of Fairoz and the Rahbani Brothers. “We were looking for: ‘Where is this Lebanon you guys are talking about?’ We were always trying to find it but we never did. But thankfully he created this image, because the bond we have with our country is mainly because of him.