Beijing

CNN

,

China The country has moved swiftly to quell protests that erupted across the country over the weekend, deploying police forces at key protest sites and tightening online censorship.

Anger over the country’s increasingly expensive zero-Covid policy sparked protests, but as demonstrations grew in number in several major cities, so did a range of grievances – some calling for greater democracy and freedom Went.

Hundreds of thousands of protesters have even called for the ouster of Chinese leader Xi Jinping, who has overseen nearly three years of a strategy of mass testing, brute-force lockdowns, enforced quarantines and digital tracking that has unleashed a devastating human has come. and economic cost.

Here we know.

The protests were triggered by a deadly fire last Thursday in Urumqi, the capital of the far western region of Xinjiang. A blaze at an apartment building has killed at least 10 people and injured nine – sparking outrage after video emerged of the incident purporting to show lockdown measures preventing firefighters from reaching victims. was delayed.

The city was placed on lockdown for more than 100 days, with residents unable to leave the area and many forced to stay home.

Video shows Urumqi residents marching towards a government building and chanting slogans calling for an end to the lockdown on Friday. The next morning, the local government said it would lift the lockdown in phases – but did not provide a clear time frame or address the protests.

This failed to quell public anger and the protests quickly spread beyond Xinjiang, with residents of cities and universities across China also taking to the streets.

So far, CNN has verified 20 demonstrations in 15 Chinese cities, including the capital Beijing and the financial hub Shanghai.

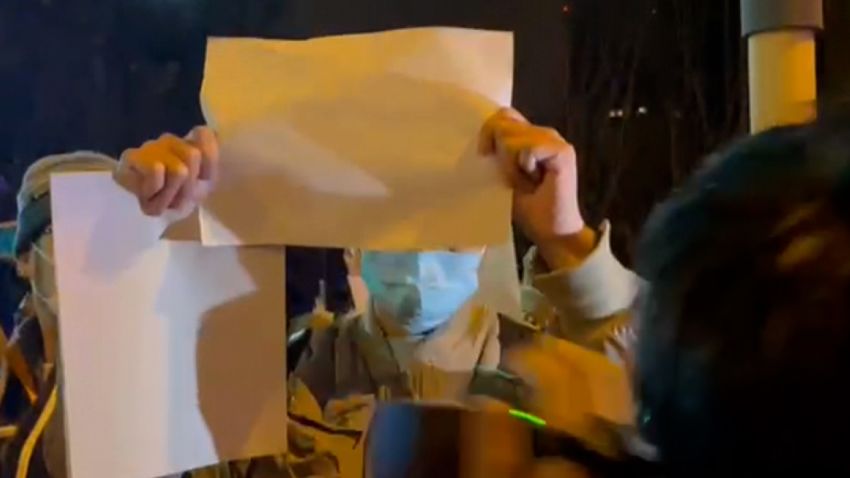

Hundreds of people gather for a candlelight march along Urumqi Road, named after the Xinjiang city, to mourn fire victims in Shanghai on Saturday. Many carried blank sheets of white paper – a symbolic protest against censorship – and chanted, “We want human rights, we want freedom.”

Some even shouted for Xi to “step down”, and sang The Internationale, a socialist anthem. Used as a call to action in demonstrations around the world for over a century. It was also sung during a pro-democracy protest in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989 before a brutal crackdown by armed troops.

China’s zero-Covid policies have been particularly felt in Shanghai, where a two-month-long lockdown earlier this year left many without access to food, medical care or other basic supplies – leaving people I was deeply resentful.

By Sunday evening, massive demonstrations had spread to Beijing, Chengdu, Guangzhou and Wuhan, where thousands of residents called for not only an end to Covid restrictions, but more significantly, political independence. Residents of some ghettos broke barricades and took to the streets.

Protests also took place on campuses including the prestigious institutions of Peking University and Tsinghua University in Beijing, and the Communications University of China, Nanjing.

In hong kongDozens of people gathered for a vigil Monday evening in the city’s central district, where a national security law imposed by Beijing in 2020 has been used to crack down on dissent. Some held blank pieces of paper, while others left flowers and carried placards in memory of those killed in the Urumqi fire.

Listen to protesters in China demanding Xi Jinping’s resignation

Public protests are extremely rare in China, where the Communist Party has tightened its grip on all aspects of life, launched a sweeping crackdown on dissent, wiped out much of civil society and created a high-tech surveillance state Is.

The mass surveillance system is even stricter in Xinjiang, where the Chinese government is accused of locking up to 2 million Uighurs and other ethnic minorities in camps where former detainees allege they were physically and sexually abused.

damn United Nations report in September described the area’s “invasive” surveillance network, with police databases containing hundreds of thousands of files containing biometric data such as facial and eye scans.

China has repeatedly denied allegations of human rights abuses in the region.

While protests do happen in China, they rarely happen on this scale, nor do they take such direct aim at the central government and the country’s leader, said Maria Repnikova, an associate professor at Georgia State University who teaches Chinese. Study politics and media.

“This is a different type of protest from the more local protests that we have repeatedly seen over the past two decades that focus their claims and demands on local authorities and very targeted social and economic issues,” she said. Instead, this time the protest has been expanded to include “concerns about the Covid-19 lockdown as well as a sharp expression of political grievances”.

After nearly three years of economic hardship and disruption to daily life, there are growing signs in recent months that the public has run out of patience with zero-Covid.

Protests broke out in different places in October, inspired by a banner, with anti-Zero anti-Covid slogans appearing on the walls of public toilets and in various Chinese cities. Lonely protester on an overpass in Beijing Just days before Xi’s third term in power.

Earlier in November, there were large protests in Guangzhou, with residents defying orders to remove roadblocks and cheering as they took to the streets.

While protests in many parts of China spread largely peacefully over the weekend, authorities responded more forcefully in some cities.

The Shanghai protests on Saturday led to scuffles between demonstrators and police, with arrests made in the early hours of the morning. Protesters returned on Sunday, where they were met with a more aggressive response – videos show chaotic scenes of police pushing, dragging and beating protesters.

The video has been removed from the Chinese Internet by censors.

A Shanghai protester told CNN he was one of about 80 to 110 people detained in the city on Saturday night. He described being transferred to a police station, having his phone confiscated and biometric information collected before being released a day later.

CNN cannot independently verify the number of people arrested.

Two foreign journalists were also briefly detained. BBC journalist Edward Lawrence He was arrested in Shanghai on Sunday night, with a BBC spokesman claiming he was “beaten and kicked by police” while covering the protests. He has since been released.

Video shows British journalist ‘beaten’ and detained in China

On Monday, a spokesman for China’s foreign ministry said Lawrence did not identify herself as a journalist before being taken into custody.

Michael Peuker, China correspondent for Swiss public broadcaster RTS, was reporting live when he said several police officers approached him. He later posted on Twitter that officers took him and his cameraman into a vehicle before releasing him.

A spokesman for China’s foreign ministry on Monday deflected questions about the protests, telling a reporter who asked whether the widespread display of public anger would lead China to consider ending zero-Covid: “What you mentioned It doesn’t reflect what really happened.”

He also claimed that social media posts linking the Xinjiang fires to COVID policies had “ulterior motives” and that officials are “making adjustments based on realities on the ground.” When asked about the protesters asking Xi to step down, he replied: “I am not aware of the situation you mentioned.”

State-run media have not directly covered the demonstrations – but praised zero-Covid, with one newspaper on Sunday calling it the “most scientifically effective” approach.

In recent days, marches and demonstrations expressing solidarity with protesters in China have been held around the world, including in the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia.

As news of the protests made international headlines, foreign government officials and organizations voiced their support for the protesters and criticized Beijing’s response.

“We’re watching this as closely as you can expect we will,” US National Security Council Coordinator for Strategic Communications John Kirby said on Monday. “We continue to stand by and support the right to peaceful protest.”

Why are protesters in China holding the white paper?

Britain’s Foreign Secretary James Cleverly told reporters that the Chinese government should “listen to the voices of its own people … when they are saying that they are not happy with the sanctions imposed on them.”

The European Broadcasting Union (EBU) also said on Monday that it condemned the “intolerable threats and aggression” directed towards member journalists in China in the context of foreign journalists being detained.