Despite direct economic consequences, study finds most Arabs don’t care about Ukraine-Russia war

LONDON: Most people in the Middle East and North Africa don’t care much about the war in Ukraine, according to an exclusive Arab News-YouGov poll.

However, experts say there are many reasons to do so.

“It seems to be going too far,” said Abir Etefa, a Cairo-based senior spokesman for the United Nations World Food Program in the Middle East and North Africa.

Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, is more than 3,000 kilometers from Riyadh.

“But at the same time, the politics and dynamics of the conflict in Ukraine are too complex for audiences in the region.”

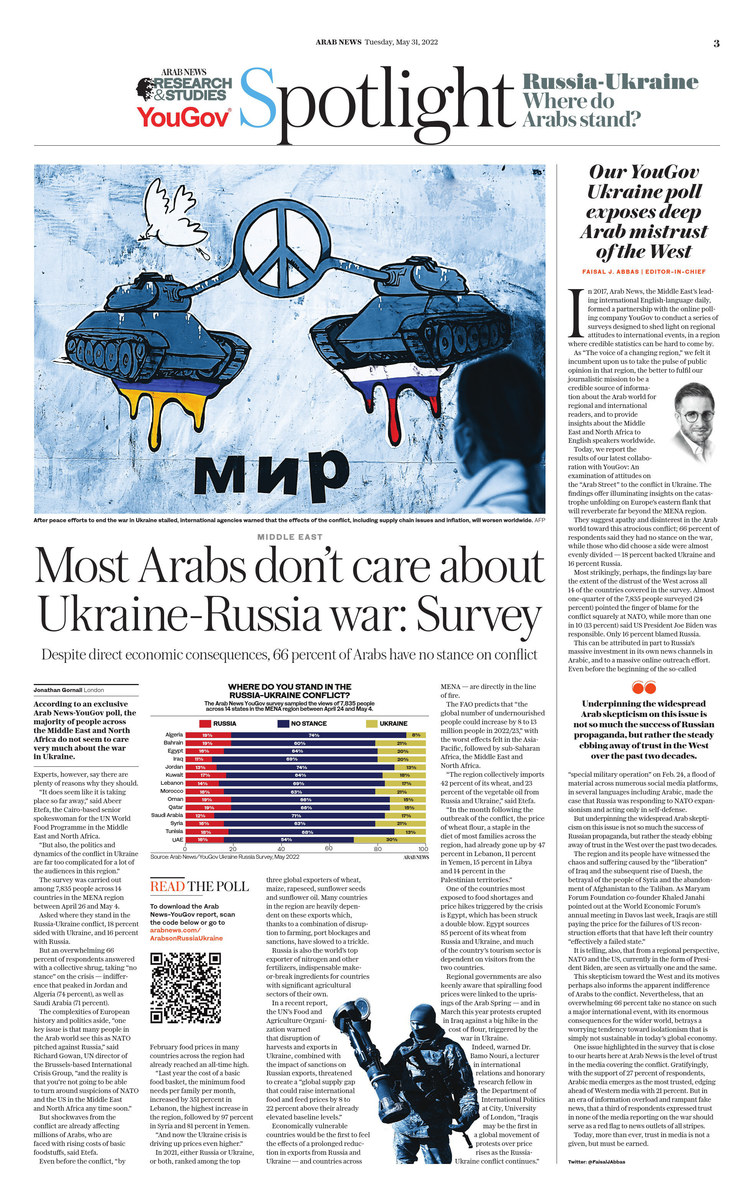

The survey was conducted between April 26 and May 4 among 7,835 people from 14 countries in the MENA region.

When asked where they stand in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, 18 percent sided with Ukraine and 16 percent with Russia.

But an overwhelming 66 percent of respondents responded with a collective shrug, opting to take “no stance” on the crisis – apathy that peaked in Jordan and Algeria (74 percent) and Saudi Arabia (71 percent).

Leaving aside the complexities of European history and politics, Richard Govan, UN director of the Brussels-based International Crisis Group, sees another reason for the apparent indifference of many Arabs to events in Ukraine.

“We are seeing a huge gap between the way Americans and Europeans view this conflict and how it is viewed in other parts of the world,” he said.

“A major issue is that many people in the Arab world see this as NATO’s stand against Russia, and the reality is that you are not able to dispel NATO and US suspicions in the Middle East and North Africa. Will be. Time soon.”

Although the reasons behind the fighting and conflict in Ukraine really have nothing to do with the Arab world, the tremors of the conflict are already affecting millions of Arabs who are facing rising prices of basic food items. , Etefa said.

He added that even if the fighting stops tomorrow, “the world will need between six months and two years to recover from a food security perspective.”

Even before the conflict, she said, “Food prices had already reached their highest levels in many countries across the region by February.

“Last year the cost of a basic food basket, the minimum food requirement per month per family, increased by 351 percent in Lebanon, the region with the highest growth, followed by Syria at 97 percent and Yemen by 81 percent.

“And now the Ukraine crisis is driving the prices even higher.”

Experts were hopeful that wheat from India would make up for some shortfall from Ukraine, but last week the Indian government banned exports after crops in the country were hit by a heatwave that pushed prices of some food items to record highs .

Even before the conflict, WFP was providing aid to millions of people across the region in Yemen, Lebanon and Syria. Now, even as the demand for its resources increases rapidly as a result of events in Ukraine, rising food and oil prices mean that the WFP’s own costs have risen alarmingly.

“This is happening at a very difficult time for the World Food Program,” Etefa said.

“The war in Ukraine has increased our global operating costs by $71 million a month, reducing our ability to help those in the region at a time when the world is facing a year of unprecedented hunger.

“This means that each day, globally, there are four million fewer people we can assist with daily rations of food.”

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in the (opinion area)

Many countries in the region are heavily reliant on food exports from Russia and Ukraine, which, thanks to a combination of farming disruptions, port blockades and sanctions, have slowed to a degree.

Both Russia and Ukraine are among the most important producers of agricultural commodities in the world – in 2021, Russia or Ukraine, or both, are among the top three global exporters of wheat, corn, rapeseed, sunflower seeds and sunflower oil.

Russia is also the world’s top exporter of nitrogen and other fertilizers, an indispensable make-or-break material for countries with significant agricultural sectors of their own.

In a recent report, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations warned that crop and export disruptions in Ukraine, coupled with the impact of sanctions on Russian exports, threatened to create a “global supply gap that could lead to international food and feed production.” 8 to 8. 22 percent above their already high baseline levels.”

Economically vulnerable countries will be the first to feel the effects of a prolonged reduction in exports from Russia and Ukraine – and the countries of MENA are directly in the line of fire.

The FAO predicts that “the global number of malnourished people could increase by 8 to 13 million in 2022/23,” with the worst effects felt in the Asia-Pacific, followed by sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and northern Africa is the place.

“The region collectively imports 42 percent of its wheat, and 23 percent of vegetable oil from Russia and Ukraine,” Etefa explained.

“In the month following the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine, the price of wheat flour, which is a staple in the diets of most families across the region, had already risen by 47 percent in Lebanon, 11 percent in Yemen, 15 percent in Libya. and 14 percent in the Palestinian Territories.”

Egypt, one of the countries most affected by food shortages and price hikes due to the Ukraine crisis, has been dealt a double blow. Egypt gets 85 percent of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine, and a large part of the country’s tourism sector is dependent on visitors from both countries.

In early February, just before the Russian invasion, Egypt was already suffering from high global wheat prices and the government was considering controversial reforms to an expensive national bread subsidy scheme.

Under the plan, which costs the government $5.5 billion at 2022 prices, more than 60 million Egyptians receive five loaves of bread a day for just $0.5 a month.

Regional governments are also well aware that increases in food prices in various countries were linked to the uprisings of the Arab Spring – and in March this year in Iraq protests against large increases in the price of flour triggered by the war in Ukraine got started.

Indeed, Dr Bamo Nouri, a lecturer in international relations at the City University of London and an honorary research fellow in the Department of International Politics, warned, “Iraqi may be the first in a global movement of protest over price increases as the Russia-Ukraine conflict continues.” ..”

“There has actually been a trend in various Middle East countries where there is no specific stance on the Russia-Ukraine conflict,” he said.

One reason was that in many Middle Eastern states, “the responsibility of resolving any crisis is placed on the government, and until it returns to normalcy, the reaction or debate around it will be minimal.”

He added: “In stable oil-rich Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, this may be appropriate, as the government has the means and infrastructure to keep the domestic impact of any external crisis to a minimum.”

On the other hand, in less stable regional states, such as Iraq and Lebanon, “a large section of society watches external events closely, as they are aware of the repercussions and try to actively plan and manage the situation.” , because the government does not have the capacity to do so.”