So Paulo: Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the number of Muslim converts in the poor outskirts and slums of Brazil’s major cities.

New mosques have been established in neighborhoods without a history of welcoming immigrants from the Middle East.

No one knows for sure the size of Brazil’s Muslim population. In 2010, when the most recent census was conducted by the government, 35,000 Brazilians declared themselves Muslims, a very small proportion of the total population of 210 million. Many in the country believe that the number is much higher now.

In 2012, Cesar Kaab Abdul founded a mosque in the Garden of Physical Culture, a slum in the city of Embu das Artes, in the metropolitan area of So Paulo.

A community organizer for decades, he was part of the first generation of hip hop artists in Brazil in the 1980s, and became known as a rapper and cultural activist in that region.

Caesar’s Mosque was named after Sumayya bint Khayyat, a member of the Prophet Muhammad’s community.

“I chose a woman’s name to show that the idea that women are oppressed in Islam is just a prejudice,” she told Arab News.

Caesar’s first contact with Islam was through the autobiography of Malcolm X, which is commonly circulated among black resistance movements.

“Most rappers had Malcolm X as a reference, but his religiosity usually went unnoticed,” he said.

As an office clerk in the financial district of So Paulo, Caesar had a Muslim Arab co-worker and became curious about his leisure to pray during office hours. “He told me he was Muslim, and I remember the story of Malcolm X,” he recalled.

Caesar kept on rapping and achieved some success. His band also performed at US rapper Ja Rule’s concert in Brazil.

But he was interested in Islam and was constantly looking for information about it online.

In 2007, he came into contact with a Muslim preacher in Egypt, who instructed him and sent him books about Islam. From that time on, Caesar’s life began to change profoundly.

“I used to be very radical on the cultural and political aspects of Islam … but then I began to understand the true nature of it,” he said.

Caesar performed Hajj in 2014, which was “a deeply transformative experience”. At that time, he had stopped attending concerts and drinking alcohol. Along with his mosque, he established a center for the spread of Islam.

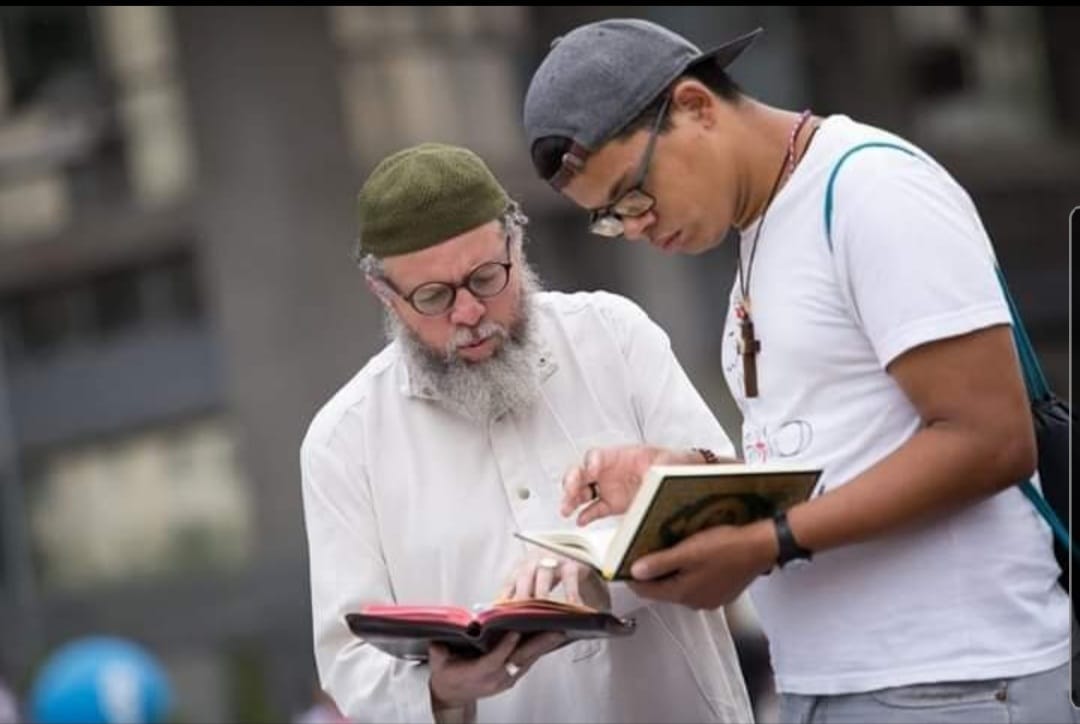

Many of his hip hop colleagues followed his example and converted to Islam. Caesar began to use his cultural influence to spread the message of the Prophet, even distributing the Quran to high-profile Brazilian rappers such as Dexter and Mano Brown.

supply

His mosque became a social hub, and distributed at least 30 tonnes of food to the needy in the region during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A fruit of his work was the conversion of Kareem Malik Abdul, the master of capoeira, a combination of dance and martial arts created by African slaves during the slavery era in Brazil (1500–1888).

“Capoeira has links to Afro-Brazilian religions,” Karim told Arab News. “At first I resisted the idea of going to the mosque when Caesar invited me, but then I saw how Islam changed his life.”

A longtime member of a capoeira group, he did not like jokes about him by his colleagues after his conversion.

“Sometimes, in front of everyone in the gym someone used to say that I was carrying bombs in my bag. As a Muslim, I was seen as a terrorist,” said Karim, who decided to leave his allies and start his own capoeira group.

“They saw capoeira as fighting and could be violent at times. In my group, I decided to focus on the musical, cultural and historical dimensions of capoeira, while emphasizing the human aspect.

Karim said the idea of taking extra care of all participants with physical safety and limitations came from Islam.

He developed a teaching method based on inspiration that attracted children with Down syndrome to his classes.

A black terrorist, he usually tells his students about the Malians, who were called Muslim Africans – usually brought from West Africa – during Brazil’s slavery era, especially in the 19th century.

In 1835, he led a famous rebellion for independence in Salvador, the capital of the state of Bahia.

“I’m sure some gardeners were capoeira fighters,” said Karim, who celebrated when another capoeira master converted to Islam because of his work.

Jamal Adessozi, a 40-year-old biologist and rapper from the city of Pelotas, is also an enthusiast of Malian history.

A black terrorist, he first discovered Islam after watching a film about Malcolm X. Years later, he sought the help of Palestinian immigrants in his city to learn more about the religion.

“I visited mosques in Rio de Janeiro and So Paulo, and at times I felt discriminated against for not being Arab and for being black,” he lamented.

Over the years, Adesoji met many African Muslims and began to feel part of a united identity.

“I studied and found that in the 19th century there were Mali and even Islamic schools in my city,” he said.

“Islam first arrived in Brazil with Africans, so it is part of our identity – a part that has been eroded over time.”

Adesoji frequents a mosque in the city of Paso Fundo, built years ago by Muhammad Lucena, a convert from So Paulo.

supply

1,000 people gather in the mosque. About 150 of them are Brazilian converts, while others are West African and South Asian, mostly working in halal units at meat and poultry processing plants.

Lucena was a black terrorist in So Paulo, whose group began to collectively study the actions of Malcolm X in the early 1990s.

He decided to visit a nearby mosque to learn more about Islam. Lucena and a friend converted.

In 1997, he received a scholarship to study in Libya – a turbulent time caused by international sanctions imposed on the regime of Muammar Gaddafi.

After a hard time settling for his new life – he spoke only Portuguese and knew no one in Libya – Lucena managed to learn Arabic and studied at university for three years.

“When I came back to Brazil, all I had in mind was to spread the message of the Prophet,” he said.

Lucena was invited to work in the halal industry in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. “Many Brazilians converted after meeting their Muslim colleagues at the processing plant, especially those from the poorest areas of the city,” he recalled.

The rapid growth of the Paso Fundo community attracted the attention of a Kuwaiti donor, and Lucena was able to buy a building and establish a mosque.

“Some of the Brazilian families who left the city and went back to their native areas also formed Muslim communities there,” he said.

Lucena believes that Islam will continue to grow in the country as more Brazilians join in its spread.

Syrian-born Jihad Hammadeh, a prominent sheikh in Brazil, told Arab News: “Brazil erased great Muslim African figures from its history. Compensation is necessary at every level while the rights of blacks are not respected.”

He celebrates the fact that many sheikhs in the country are now able to guide converts through their journey, avoiding potential distractions.

“Although Brazil’s Islam was consolidated by Arab immigrants, things have changed now,” Hammadeh said.

“Until recently, it was unimaginable that a convert could assume the leadership of an Islamic institution. Now it is more and more common.”