Digitized battle records of Indian soldiers killed in WWI Iraq expose long forgotten siege

London: The beautifully handwritten note on the Yellow Service Record, compiled by the Punjab government in 1919 and now more than a century old, is as poignant as it is concise.

In faded ink, The Entry for Vasava Singh, son of a Jat Shera from Gaik village in northeastern Punjab, tells the story of a young life in the service of a foreign empire.

There is no date, only one rank – Havildar, equivalent to Havildar – and the name of a unit, 30th Punjabi.

A document documenting the military service of over 300,000 men from Punjab was recently discovered at the Lahore Museum in Pakistan. (supplied)

An infantry regiment first formed by the British Indian Army in 1857, the 30th saw action in the Indian Rebellion (1857–58), the Bhutan War (1864–66), the Second Afghan War (1878–80) and finally the British Indian War. First World War.

It was in this last conflict, in which more than 1 million Indian soldiers fought in almost every theater of war for the British Empire, in which Singh died along with more than 70,000 of his countrymen.

Documenting his service, and the surviving paperwork of more than 300,000 other men from Punjab, have been discovered in the depths of the Lahore Museum in Pakistan. Searched after being forgotten for more than 100 years, all 26,000 pages have been digitized and can now be searched online by the name of the soldier, his father or his village.

Although a priceless treasure to both historians and the descendants of the old warriors, the documents contain only limited information. For example, they do not disclose how old Singh was, when he was killed, how he died, or even when and where he died.

However, a brief entry in the neat handwriting of some forgotten bureaucrat records that after her death, Singh’s unnamed and undoubtedly bereaved mother was awarded a small pension.

For four long years, British and Indian troops fought side by side to drive the Ottoman Empire out of what is now modern Iraq. (alami)

According to Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, 153 people named Singh died while serving with the 30th Punjabis. Vasava, service number 3902, fell on January 15, 1917 while fighting the Germans in East Africa. Although destroyed 5,000 km from his home of Punjab, he was spared, at least, the horrors of the Western Front at Gallipoli or France, where many Indians fought and suffered under dire conditions.

However, death was to be his lot. He was killed in fierce fighting, which saw the Germans finally be defeated at Mahenge near the Rufiji River in modern Tanzania.

The final resting place of Vasava Singh is unknown. His name, and the names of more than 1,200 British and Indian officers and men “whom the fate of war deprived their comrades of the known and respected burial given in death,” is recorded on the wall of the British and Indian Memorial in Nairobi South Cemetery. Is. Kenya.

QuickFact

The siege of Kut al-Amara, 160 km southeast of Baghdad, lasted four months, ending on April 29, 1916.

* Around 4,000 people died in the siege, while more than 23,000 were killed or wounded while attempting to relieve a besieged force.

Today, for the hundreds of thousands of families in India and Pakistan whose great-grandfathers and great-grandfathers took up arms for the British cause in the wars of 1914–1918, the emergence of the Lahore Museum of Papers is another step towards a long-pending recognition. The sacrifices made by so many people from the subcontinent.

In Britain, each year, the nation still observes a minute’s silence on Armistice Day: on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, the guns went silent on the Western Front in France in 1918.

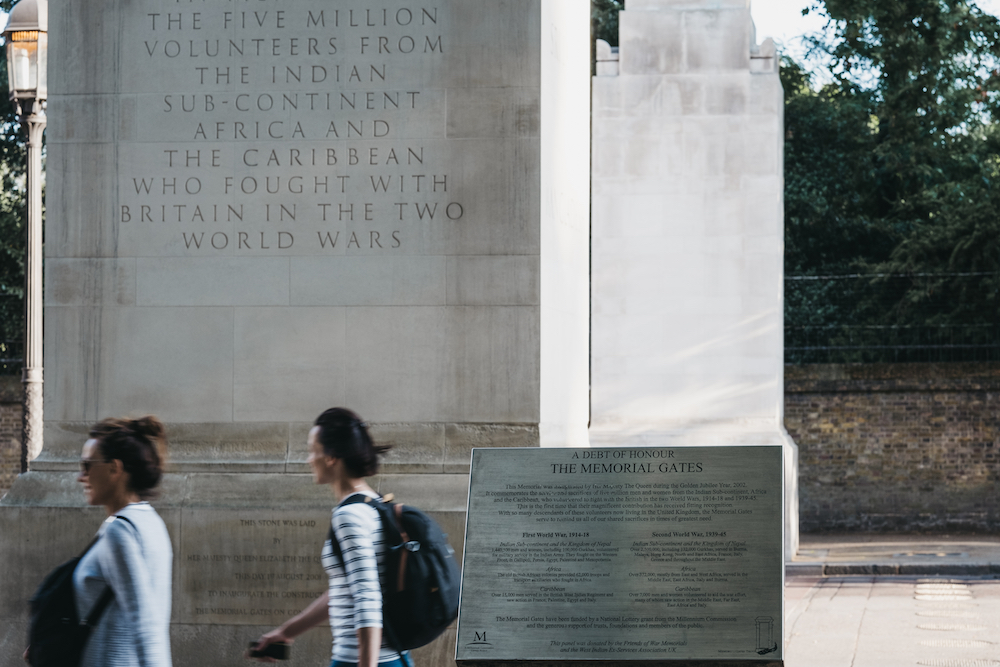

But although efforts have been made in recent years to ensure that the commemoration of Armistice Day includes all nations of the British Empire whose soldiers lost their lives, it was not until 2002 – 84 years after the end of the war – that A memorial monument dedicated to “in memory of 5 million volunteers from the Indian subcontinent, Africa and the Caribbean” was unveiled on Constitution Hill in London.

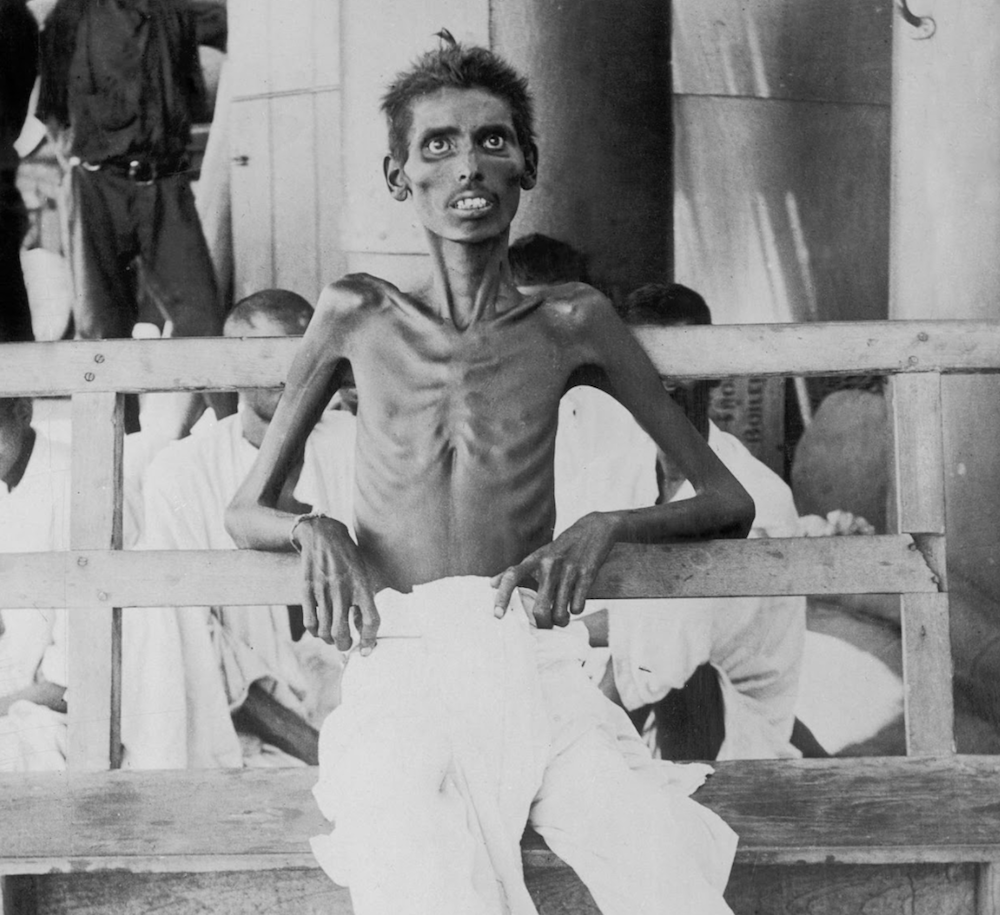

One of the Indian soldiers after being held by the Turks in a Mesopotamian prison after the fall of Kut. June 28, 1917. (Daily Mirror/MirrorPix/MirrorPix via Getty Images)

It was almost as if, in all those years, the sacrifices made by the soldiers of the subcontinent on behalf of the Empire were taken lightly.

This, of course, was the only conclusion that could be drawn from a report by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which set up a committee in 2019 to “investigate the early history of the Imperial War Graves Commission along the way The organization observed, to identify the inequalities therein”. The dead of the British Empire.”

Established a century ago as the Imperial War Graves Commission, initially to commemorate the Empire’s World War I dead, the organization was initially charged with treating all fallen people with equal respect. In a paper prepared for the commission in 1918, Lieutenant Colonel Sir Frederick Kenyon, director of the British Museum, wrote that “the final resting places of Indians and other non-Christian members of the Empire should be given no less respect. Our British soldiers For. “

In its report published earlier this year, the committee concluded that, “although the organization upheld its promise of equality of treatment in Europe, this was not always the case for some other ethnic groups.”

It found that, “contrary to the organisation’s founding principles,” between 45,000 and 54,000 casualties—primarily Indian, East African, West African, Egyptian and Somali—were “disproportionately observed.”

Memorial Gates at the end of Constitution Hill in London. (shutterstock)

Even more shocking is that at least 350,000 others “were not remembered by name or possibly at all.”

Of all the conflicts in which Indian soldiers fought and were killed with hardly any recognition, few are known, certainly in Britain, as the Mesopotamian Campaign, in which India made its greatest contribution to World War I. . As British Colonel Patrick Cowley, a veteran of the later conflict in Iraq, wrote in his 2009 book “Kut 1916: Courage and Failure”, “the campaign in Mesopotamia is a ‘forgotten war’ and Kut’s story follows the events elsewhere.” was covered.”

For four long years, British and Indian troops fought side by side to drive the Ottoman Empire out of what is now Iraq. It was a brutal, bloody affair, ultimately successful, but marred by the disaster of the siege of Kut al-Amara, a town nestled in a diversion in the Tigris 160 km southeast of Baghdad.

The siege lasted for four months. It ended on April 29, 1916, mainly with the surrender of 12,000 Indian soldiers. After four desperate months he was starving, weak from illness and cut off from any hope of relief.

The day before the surrender, a British officer wrote in his journal: “We are a sick army, a skeleton army trembling with cholera and disease.”

In all, about 4,000 people were killed during the siege. Astonishingly, 23,000 more soldiers – again, mainly Indians – were killed or wounded during efforts to relieve the besieged force.

British casualties being brought down a gangway by steamer by orders of the Indian Army at Falarieh, Mesopotamia. The Indian Expeditionary Force, consisting of both British and Indian units, advanced along the Tigris to Baghdad in the summer of 1915. (alami)

Among the defenders were men from the 22nd, 24th, 66th, 67th and 76th Punjabis. He was faced with several other Indian units, including the 117th Mahratta, 103rd Mahratta Light Infantry, 120th Rajputana Infantry and a squadron of 7th Haryana Lancers.

More Punjabi regiments, including the 28th and 92nd, were part of the relief force, which failed to fight through Kut in time, suffering a high percentage of casualties, along with other Indian units including the 51st and 53rd Sikhs and 9th Bhopal infantry. .

At least a third of the 12,000 men held captive in Anatolia, Turkey, died. Some succumbed to disease and starvation, while others were shot or beaten to death for falling behind in March, or simply left to die after falling, exhausted, on the side of the road. At one point in the march, the bodies were dumped in a ravine, where skulls were found later in battle.

Ottoman brutality spread to the local Arabs who had helped the British. About 250 were shot after the surrender, while several interpreters were hanged in Kut’s town square.

Today, the siege remains virtually unknown, certainly in Britain. However, it is considered one of the biggest disasters ever for the British Army. To this day the Kut is studied by military strategists around the world as an example of the threat of an invading army to augment its supply lines.

According to Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, 153 people named Singh died while serving with the 30th Punjabis. (alami)

Most of the Indians who fell in the kut or died in captivity have no known graves. Many are recorded on the Basra Memorial, which was constructed in 1929 and was originally located in Maqil on the west bank of Shatt-al-Arab. In 1997, by order of Saddam Hussein, it was disassembled and rebuilt 32 km along the road to Nasiriyah, in the middle of a major battlefield during the First Gulf War.

Today, the monument is in poor repair. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission stated that “while the current climate of political instability persists, it remains extremely challenging for Iraq to manage or maintain its cemeteries and monuments located within it.”

But when it finally feels capable of refurbishing the Basra monument, the CWGC will have more than just masonry and marble to repair.

According to the report of the Special Committee to Review Historical Disparities in Commemoration, “Known issues with missing monuments include 38,696 Indian casualties on monuments (only) numerically commemorated,” with their names missing.

Subsequently, names have been added to the Port Tewfik Monument in Egypt and the Joint British and Indian Monuments in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. But “no decision has yet been taken regarding the Basra memorial, mainly due to the ongoing instability in Iraq.”

The names of 7,385 British personnel and Indian officers who lost their lives in Mesopotamia can be seen on the panels of the memorial.

But for the 33,256 noncommissioned officers and other ranks of the British Indian Army, who are numbered but unnamed at the Basra memorial, the humiliation of anonymity is not yet over.

,