JEDDAH: Many breathed a sigh of relief as 2022 drew to a close, marking the conclusion of 12 months of post-pandemic fatigue, geopolitical tensions and global economic instability, to name but a few of the challenges of the past year.

One result of the year’s volatility and volatility is a widespread sense of anger coursing through societies, fed by a litany of back-to-back crises – solutions to which appear to have eluded governments and global institutions.

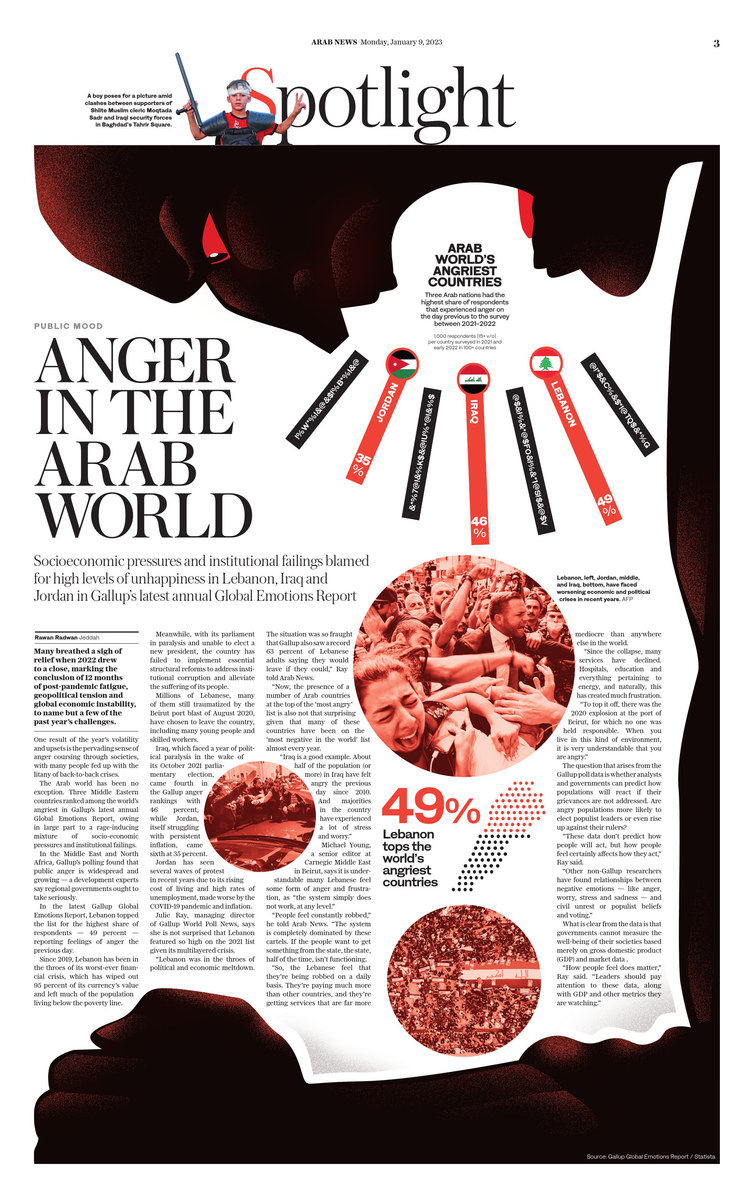

The Arab world has been no exception. Gallup’s latest annual Global Sentiments report ranked three Middle Eastern countries among the world’s angriest countries, due in large part to an anger-inducing mix of socioeconomic pressures and institutional failures.

Angry Jordanians gather in the city of Salt to protest the death of at least six COVID-19 patients at a hospital that ran out of oxygen, March 13, 2021. (AFP File)

Just as the world economy looked to recover from the lockdowns, supply-chain disruptions and travel restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine fueled inflation, taking a heavy toll on food and fuel prices for the world’s poorest I.

Add to this political instability, corruption and the corrosive effects of suspected climate change, and the past year has surprisingly proved to be a period of rising anxiety, crippling anger and violent unrest for millions of people around the world.

In the Middle East and North Africa, where price volatility, climate shocks and protracted political crises have been acutely felt, Gallup polling finds public anger is widespread and growing – development experts say That the regional governments should be taken seriously.

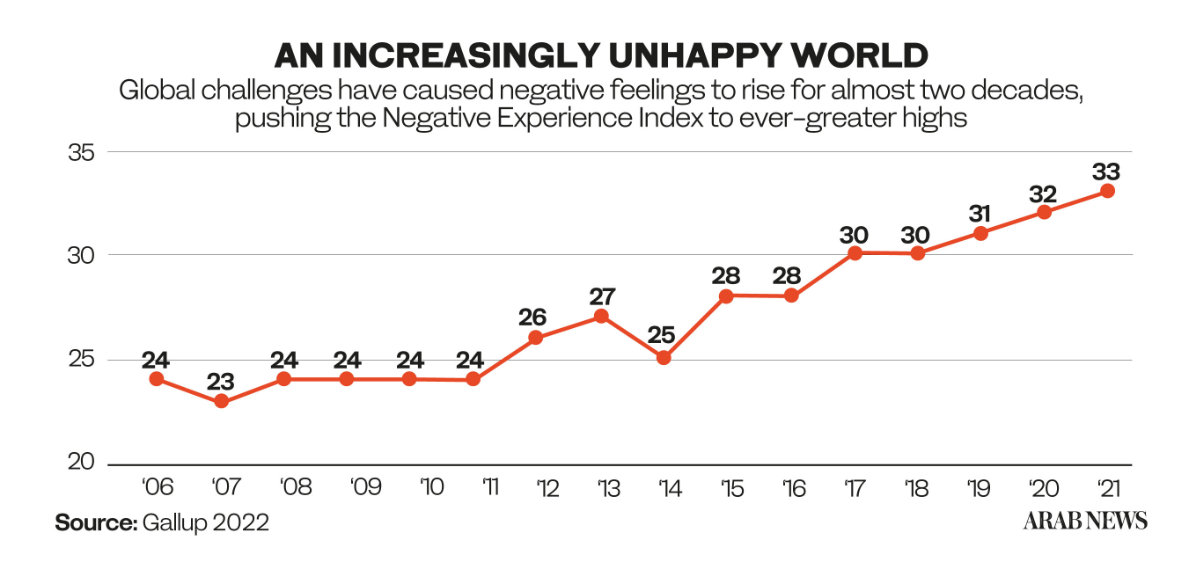

Gallup first began tracking global unhappiness in 2006, with a methodology based on a nationally representative, probability-based sample among adult populations aged 15 and older, collected from 122 countries.

It found that negative emotions – the sum total of stress, sadness, anger, anxiety and physical pain – reached a record high last year, with 41 per cent of adults globally saying they had experienced stress in the previous day.

Furthermore, these negative sentiments appear to be increasing, with 2021 displacing 2020 as the most stressful year in recent history.

Over the past decade, the Arab world has been wracked by mass protests, regime collapse, corruption, scandals, wars and mass exodus, disrupting regional priorities and internal dynamics.

Iraqis block a road in the southern city of Nasiriyah on December 11, 2022, to protest the deaths of fellow protesters in clashes with security forces. (AFP File)

In the latest Gallup Global Emotions Report, Lebanon tops the list for the highest share of respondents – 49 percent – reporting feelings of anger in the past day.

Since 2019, Lebanon has been in the grip of its worst financial crisis, which has wiped 95 percent off the value of its currency and left most of the population living below the poverty line.

Meanwhile, with its parliament paralyzed and unable to elect a new president, the country has failed to implement structural reforms needed to address institutional corruption and ease the suffering of its people.

Activists and relatives of victims of the Beirut port explosion scuffle with security officers during a demonstration in the Lebanese capital September 29, 2021. (AFP File)

Millions of Lebanese, many of whom are still in shock from the Beirut port explosion of August 2020, have chosen to leave the country, including many young and skilled workers, fed up with poor conditions and lack of opportunities.

Iraq, which faces political paralysis in the wake of an October 2021 parliamentary election, came in fourth in the Gallup anger rankings with 46 percent, while Jordan, itself battling persistent inflation, came in sixth at 35 percent.

Jordan has seen several waves of protests in recent years due to its rising cost of living and high rates of unemployment, made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic and inflation.

FastFact

Lebanon ranked first with 49% of respondents reporting feelings of anger in the past day.

Iraq, which faced a year of political paralysis following its 2021 election, came in fourth with 46%.

Jordan, which is battling rising inflation and high unemployment, dropped to sixth place at 35%.

(Gallup Global Emotions Report)

Julie Ray, managing director of Gallup World Poll News, says she’s not surprised Lebanon is so high on the 2021 list given its multi-layered crisis.

“Lebanon was in the grip of a political and economic meltdown. People were struggling to keep food on their tables and taking to the streets. The situation was so dire that Gallup found a record 63 percent of Lebanese adults saying they would leave if they could,” Ray told Arab News.

Julie Ray, Managing Director of Gallup World Poll Content. (supply)

“Now, the presence of several Arab countries at the top of the ‘most angry’ list is also not surprising as many of these countries have been on the ‘most negative in the world’ list almost every year.

“Iraq is a good example. Nearly half (or more) of the population in Iraq have felt anger on the previous day since 2010. And the majority of people in the country have experienced great stress and anxiety.

Michael Young, a senior editor at Carnegie Middle East in Beirut, says it is understandable that many Lebanese feel a form of anger and frustration, because “the system does not work on any level.”

“People feel constantly robbed,” he told Arab News. “The system is completely dominated by these cartels. If people want to get something from the state, the state is not working half the time.

“So, the Lebanese feel that they are being robbed on a daily basis. They are paying much more than in other countries, and they are receiving services that are far more mediocre than anywhere else in the world. are of.

“Since the collapse, many services have declined. Hospitals, education, and everything related to energy, and naturally, that has caused a lot of frustration. You had a lot of people who were essentially middle class people who suddenly found themselves in poverty.

“To top it off, the 2020 explosion at the port of Beirut, which killed over 200 people, destroyed half of Beirut, and no one was held responsible. When you live in such an environment, it is very understandable that you are angry.”

In this November 29, 2021 photo, Lebanese protesters block a highway during a protest in Beirut as the country grapples with a deep economic crisis. (AFP)

This continuing conflict has left many Lebanese feeling frustrated. However, Young says that expectations play an important role in feelings of resentment.

For example, compare a country like Lebanon – a middle-income country that has seen a sudden decline in services and political stability since 2019 – with the likes of Afghanistan, a poor country crippled by war for nearly half a century .

“When you have a country like Afghanistan, where it has been wracked by endless conflict and declining living standards since the 1970s, (the low expectations) are understandable,” Young told Arab News.

“If your expectations are high, and the reality falls far short of these expectations, it will anger you more than if your expectations are low and what you get in return is also relatively low.

“The question of expectations is a main generator of Lebanese frustration. The Lebanese were used to a life that suddenly, in some way, catastrophically collapsed.

Afghanistan, one of the world’s most corrupt countries and which saw the Taliban return to power in August 2021, was ranked the fifth most angriest in Gallup’s poll, with 41 percent.

Taliban security forces arrive during a demonstration by Afghan women against a suicide bombing attack at a school in Kabul on October 1, 2022 that killed 20 people. (AFP)

In recent decades, negative feelings reported in Gallup’s polling have been on the rise. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have further exacerbated this trend. But, as Ray points out, “every country is different.”

“The common thread we see in countries where negative experiences are high is crisis. All populations are going through upheaval of some sort – whether economic, political or social.

The question that the data raises, however, is whether analysts and governments can predict how populations will react if their grievances are not addressed. Are angry populations more likely to elect populist leaders or even rise up against their rulers?

“These data do not predict how people will act, but how people feel certainly affects how they act,” Ray said.

“Other non-Gallup researchers have found associations between negative emotions — such as anger, anxiety, stress and sadness — and civil unrest or populist beliefs and turnout.”

What is clear from the data is that governments cannot measure the well-being of their societies on the basis of GDP and market data alone.

“How people feel matters,” Ray said. “Leaders should pay attention to these figures, as well as the GDP and other metrics they are watching.”