Written by Don Clark

Since 1989, microchip technology has worked in an uncharted backwater of the electronics industry, creating chips called microcontrollers that add computing power to cars, industrial devices, and many other products.

Now a global chip shortage has raised the company’s profile. Demand for Microchip’s products is driving more than 50% of the supply. This has put the company based in Chandler, Arizona, in an unfamiliar position of power, which it started this year.

While Microchip typically lets customers cancel a Chip order within 90 days of delivery, it began offering shipment priority to customers who signed contracts for 12-month orders that were canceled or rescheduled. could not be done. These commitments reduced the likelihood that orders would evaporate when the shortages were eliminated, giving Microchip more confidence to safely hire workers and purchase expensive equipment to increase production.

“It gives us the ability to not hold back,” said Ganesh Murthy, president and CEO of Microchip, which reported Thursday that profits tripled in the latest quarter and sales jumped 26% to $1.65 billion.

Such contracts are just one example of how the $500 billion chip industry is changing due to silicon shortages, with many changes likely to address pandemic-fuelled shortages. The lack of small components – which have pinched manufacturers of cars, game consoles, medical devices and many other goods – is a stark reminder of the fundamental nature of chips, which served as the brains of computers and other products.

Chief among the changes is a long-term shift in market power from chip buyers to sellers, particularly those who own factories manufacturing semiconductors. The most visible beneficiaries are giant chip makers such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which provides services called foundries that make chips for other companies.

But the shortage has also exacerbated the impact of lesser-known chip makers such as Microchip, NXP Semiconductors, STMicroelectronics, Onsemi and Infineon, which design and sell thousands of chip varieties to thousands of customers. These companies, which make many products in their old factories, are now increasingly able to choose which customers get how many of their rare chips.

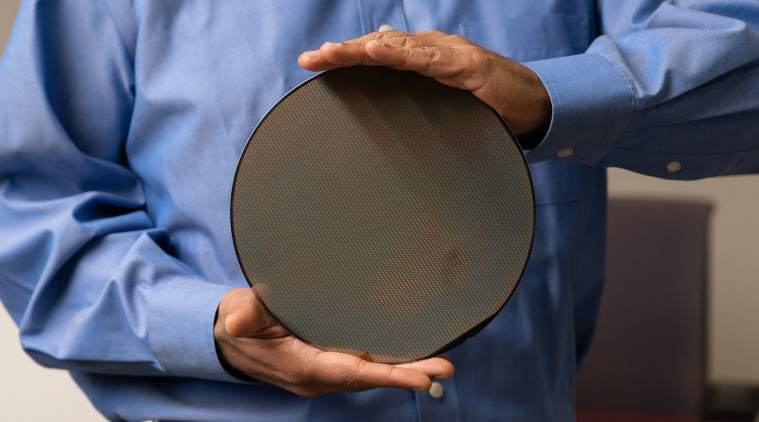

“Long-term purchase commitments from customers give us the ability to not hold back,” said Ganesh Murthy, chief executive of Microchip Technology at the company’s headquarters. (Image source: The New York Times)

Many are supporting buyers who act as partners by taking steps such as signing long-term purchase commitments or making investments to help chip makers ramp up production. Above all, chip makers are asking customers to share more information in advance about which chips they’ll need, which helps make decisions about how to pick up manufacturing.

“That visibility is what we need,” said Hassan Al-Khouri, CEO of chip maker Onsemi.

Several chip makers said they were using their new power sparingly, helping customers avoid problems such as factory closures and modest price increases. This is because defrauding customers, he said, can lead to bad blood that will hurt sales if the shortage is over.

Still, the transition to power has been unmistakable. “There is no profit for buyers today,” said Mark Adams, CEO of Smart Global Holdings, a major user of memory chips.

Silicon Valley company Marvell Technology, which designs chips and outsources manufacturing, has experienced a shift in power. While it gave foundries estimates of chip production needs for 12 months, it began providing them with five-year forecasts starting in April.

“You really need a good story,” said Marvel CEO Matt Murphy. “Ultimately the supply chain is going to allocate what they think is going to be the winner.”

This is a major change in psychology for a mature industry where growth has generally been slow. Many chip makers sold largely interchangeable products for years and often struggled to run their factories profitably, especially if sales of items such as personal computers and smartphones declined, driving demand for most chips.

But the ingredient is now needed for more products, one of many signs that rapid growth may be stalling. The Semiconductor Industry Association said that in the third quarter, total chip sales rose nearly 28% to $144.8 billion.

Years of industry consolidation have also eliminated excess manufacturing capacity and left fewer suppliers selling specialty chips. So buyers who can place and cancel orders with less notice at once — and play one chip maker over another to get a lower price — have less muscle.

One effect of these changes was to make chip factories more valuable, including those owned by some older foundries. That’s because new manufacturing processes have become so expensive that some chip designers aren’t moving to the most advanced factories to make their products. The result is a lack of demand for less-expensive production lines that are 5-10 years old.

So some foundries, in a major strategy shift, are starting to put more money into older production technology. TSMC recently said that it would build such a plant in Japan. samsung Electronics, a major foundry rival, has also said it was considering a new “legacy” factory.

But it will take years for those investments to pay off. And they won’t address issues affecting chips like microcontrollers, which are a microcosm for supply chain squeezes.

Microcontrollers combine the ability to perform calculations with built-in memory to store programs and data, often adding features that only come from specialized factories. And the number of applications is skyrocketing, from brake and engine systems in cars to security cameras, credit cards, electric scooters and drones.

“We’ve probably sold more microcontrollers in the past decade than we have in the past decade,” said Mark Barnhill, chief business officer at Smith, a Houston-based chip distributor. The wait to get some popular microcontrollers has now been over a year, and the prices of the products have risen 20 times among merchants who buy and sell chips, he said.

Amid the turmoil, companies that design or use the chips have responded with new strategies. Some designers are making their products in different factories with more manufacturing capacity, said Shiv Tasker, a global vice president engaged in that practice for consultancy Capgemini.

And customers who once bought chips based on price and performance are also thinking more about availability.

Consider BrightAI, a startup developing devices and software to help businesses connect devices and other devices to the Internet. Its co-founder Alex Hawkinson said it redesigned a circuit board four times in six months to adapt to different chips. He said the company moved some designers to China to more quickly modify products with components sourced there.

Large chip users such as automakers have begun talking directly with manufacturers rather than following the typical practice of working through subcontractors. Last month, General Motors struck a deal with chip maker Wolfspeed to ensure a portion of the semiconductors come from a new factory that makes energy-efficient components for electric vehicles.

While the power change of the chip industry has helped Microchip, it has also come with a headache of its own. Murthy said the company has managed to produce more chips at its three main factories in Arizona and Oregon, as well as have gained more from foundry partners. But the demand is growing faster than what it can produce.

“We are lagging far behind,” he said.

Expanding Microchip’s plants isn’t easy. For one thing, the company has always relied heavily on buying used manufacturing equipment, but “that whole thing has dried up,” Murthy said.

He said it may take 12-18 months to acquire the new gear and the cost is high. While long-term purchase agreements have provided greater stability for making such investments, Microchip and others also expect Congress to approve a $52 billion funding package, which will include grants to subsidize more US chip production. are supposed to.

“Are we relying on it to run our business? No,” said Murthy. “Will it help with some of our investment options? Absolutely.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

,