JEDDAH: In the absence of a safe and legal route to Europe, refugees fleeing war, poverty and persecution in their home countries are often faced with barbed wire, suspicion and outright hostility when they come to the EU’s doorstep.

For many years, the plight of migrants and refugees arriving in Europe has divided public opinion, throwing competing narratives about compassion and national identity while raising security and counter-terrorism concerns.

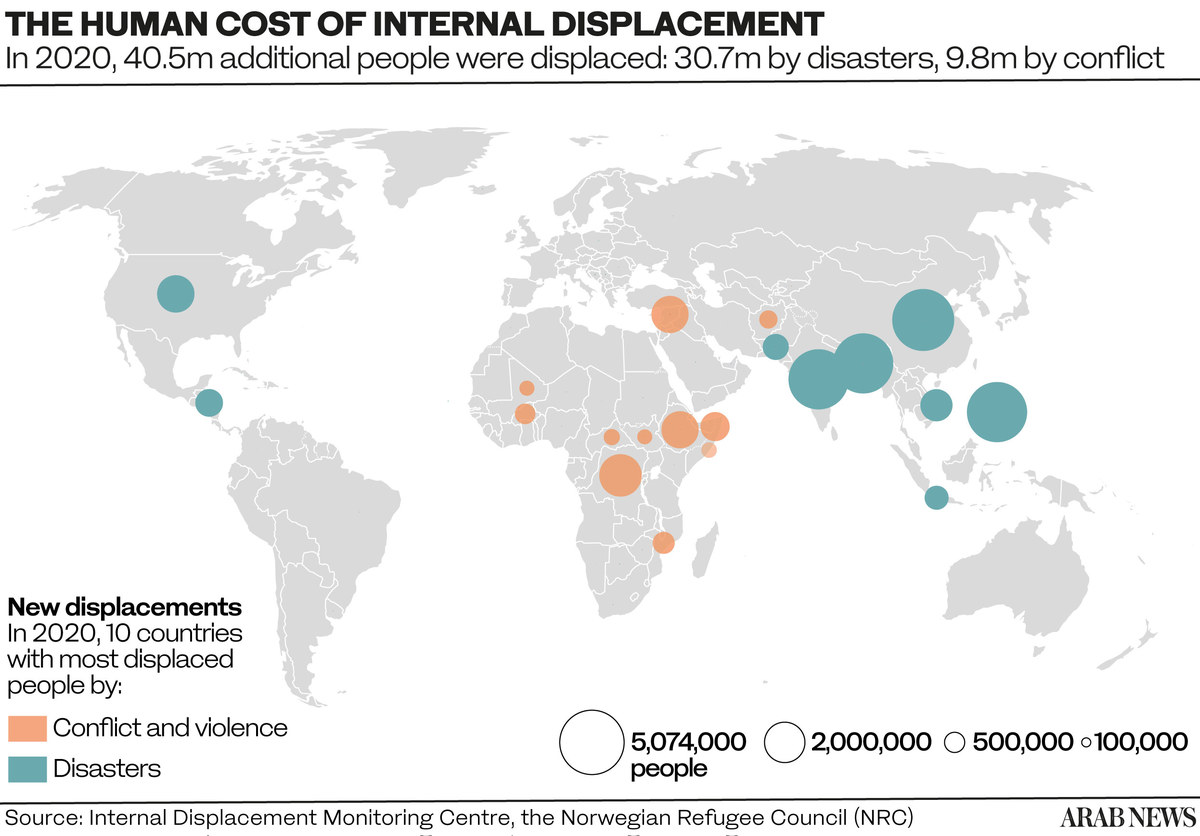

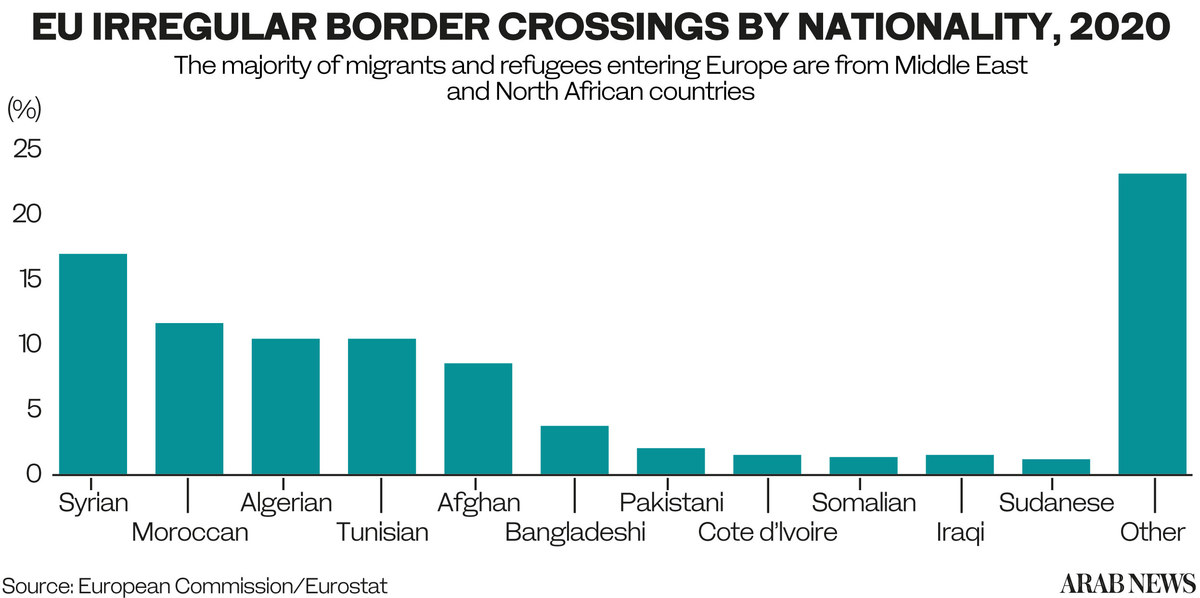

These divisions were brought to the fore in 2015, when hundreds of thousands of Syrian, Iraqi, Afghan, Iranian, Sudanese, Eritrean and other nationalities made dangerous journeys by land or sea to Europe, often with the help of smugglers.

Many of these debates resurfaced in the final months of 2021, when thousands, mainly from the Middle East, arrived at the Belarus-Poland border, camping on the bitterly cold forest border in vain hope of crossing into Europe.

Earlier in December, Poland closed its borders by building a 115-mile-long fortified wall, which is expected to be completed by June this year at a cost of about $300 million.

The fortified border walls began to appear after the 2015 influx of refugees, mainly from the Middle East. The Hungarian wall alone has cost the EU more than 1 billion euros.

A European Union flag waves behind a barbwire at the newly closed center for migrants in the Greek island of Kos on November 27, 2021. (AFP)

Similar fortifications have begun in Slovenia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Spain and France to keep migrants out.

The European Union grew from just two walls to 15 in 2017 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, which is the equivalent of six Berlin Walls. These new barriers reflect a general hardening of views against refugees in Europe.

Innumbers

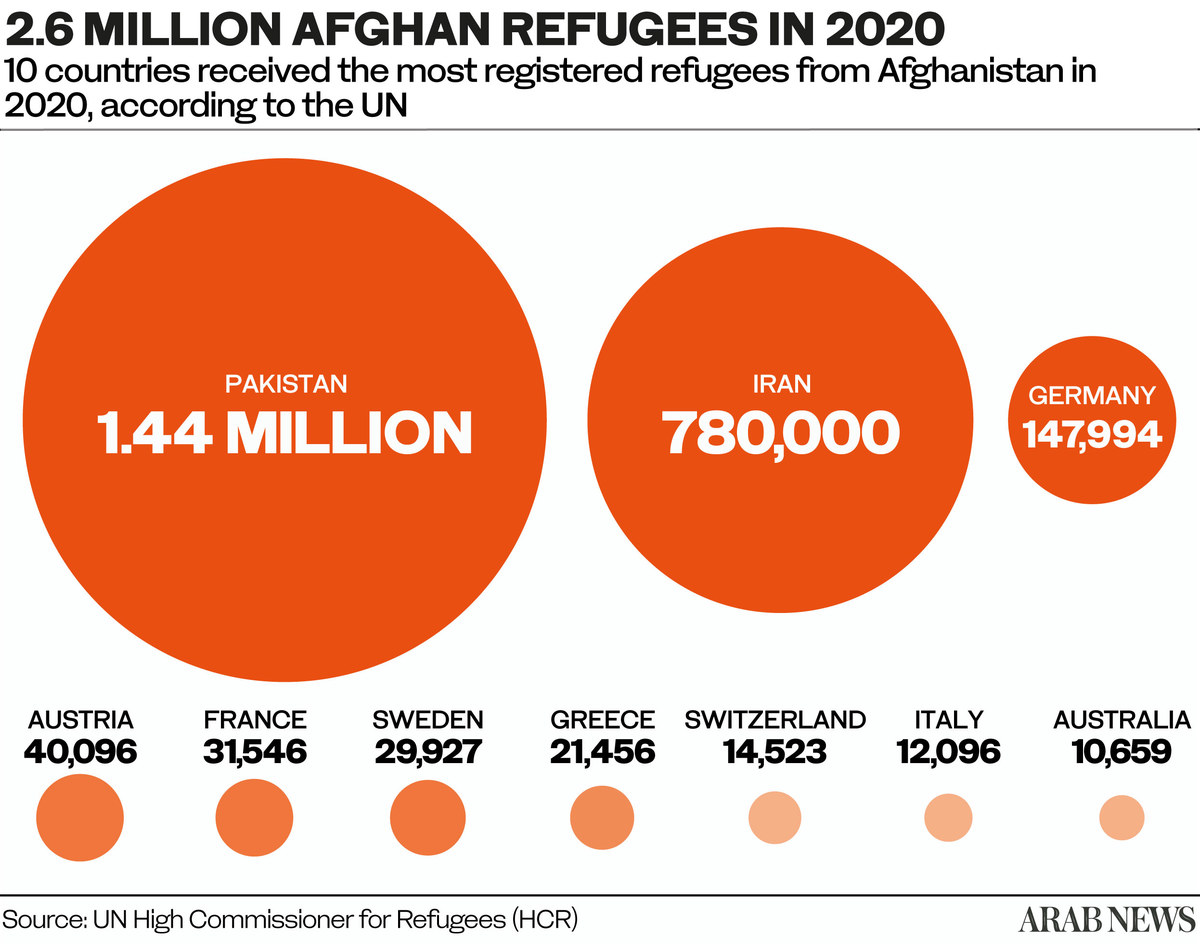

* 26.6 million – refugees globally as of mid-2011.

* 0.6 percent – the proportion of the EU population who are refugees. (UNHCR)

Where European leaders once considered taking refugees a human duty, many now draw political capital out of tough talk on illegal immigration. In the process, the issue of migration has diverged from the disasters that caused them to migrate.

“It’s inhumane to say the least,” Syrian journalist, activist and refugee Wafa Mustafa, who lives in Germany, told Arab News. “We can’t talk about refugees without talking about the reasons why they become refugees.”

Mustafa’s father, Ali, a Syrian human rights activist, was arrested in July 2013 before disappearing into Bashar Assad’s notorious prison system. About 130,000 people are believed to be lodged in the regime’s prisons, where they reportedly endure torture and sexual abuse.

Mustafa said, “We cannot ignore the fact that there are forces that drive people to risk their lives, and their children and loved ones, who are more difficult than those left to die at the borders.” Huh.”

“I think the way the EU is treating people stranded on its borders is a crime. We have been hearing about illegal entry as a crime, but I think the real crime is not letting people cross the border and leaving them to die.

Mustafa believes that European politicians refuse to engage with the issue because “they will have to face the fact that they have failed in their jobs, and that the international community has failed to address the problem, Syria’s Assad dictatorship in the case.”

A member of the UK Border Force (R) helps child migrants on a beach in Dungeness, on the south-east coast of England, on November 24, 2021, after they were rescued while crossing the English Channel. (AFP)

Given this rush to fortify its borders, many could be forgiven for thinking that the economic and social burden of the global refugee crisis fell primarily on Europe. Nothing could be further from the truth.

As the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR often points out, 85 percent (as of mid-2021) of the world’s 26.6 million refugees are hosted either in neighboring countries or elsewhere in developing regions.

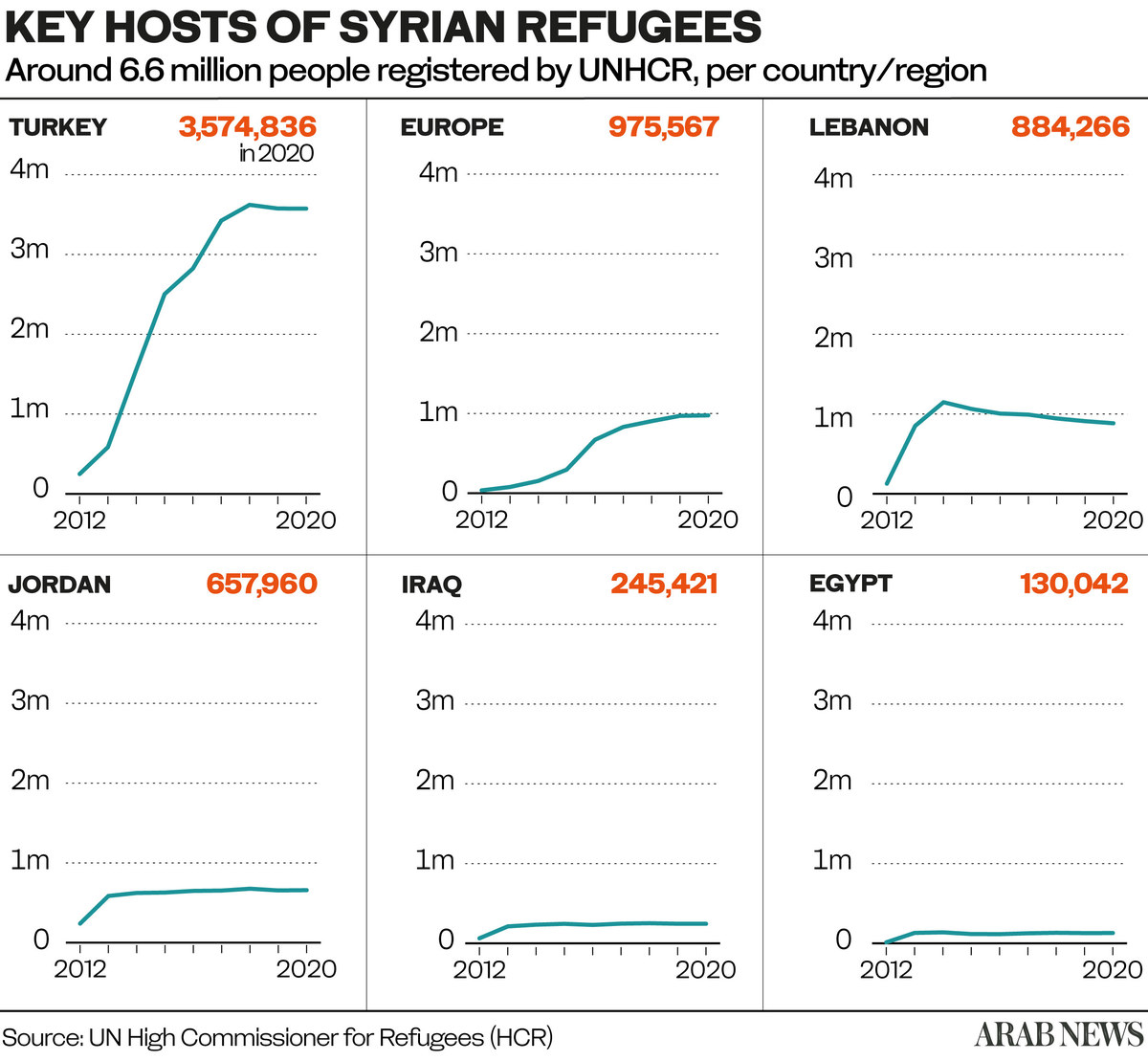

For example, Turkey has more refugees within its borders than any other country – more than 3.5 million, or 43 for every 1,000 citizens of its own. Jordan has about 3 million, while smaller Lebanon has 1.5 million – more than 13 refugees for every 100 Lebanese.

In contrast, about 2.65 million refugees live in the EU’s population of 447 million.

After World War II, European states signed treaties designed to protect the rights of refugees, including the 1951 Refugee Convention, the 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees, and the 1980 European Convention on the Transfer of Responsibility to Refugees. Is.

Despite these commitments, European leaders and sections of the media have created crude narratives of “deserving” and “unqualified” migrants to help justify turning away refugees.

“It’s a dangerous story,” Mustafa said. “We need to see them as human beings, listen to their stories and provide them with the resources to deal with the reasons they come to Europe.”

Migrants aiming to enter Poland are seen at a camp near the Brzegi-Kuznica border crossing on the Belarusian-Polish border on November 17, 2021. (AFP)

Abdulaziz Dukhan, originally from Homs in western Syria, arrived in Greece in 2015 when he was just 17 years old. It was there, while confined to one of the country’s overcrowded camps, that a volunteer gifted him a camera.

What started as a hobby soon developed into a prolific photography career when he eventually settled in Belgium.

An exhibition of Dukhan’s photographs was held in Brussels late last year, titled “50 Humans”, to challenge the scapegoating of migrants and refugees, showcasing the positive contributions he has made to multicultural societies. was scheduled for.

Innumbers

Top 5 Nationalities of First Time Asylum Applicants in the European Union (2020)

1. Syrian 63,600

2. Afghan 44,285

3. Venezuela 30,325

4. Colombian 29,055

5. Iraqi 16,275

*Source: European Commission/Eurostat

“His backstory has made him who he is, but I don’t dwell on his past,” Dukhan told Arab News. “I focus on their present, answering moral arguments in the most subtle manners. Forget wars and conflicts and focus on the now. These are their true stories.”

Opponents of accepting refugees often argue that they burden the economy, take jobs and reduce wages, or scrutinize state handouts. However, studies have shown that societies with younger working-age populations benefit from the arrival of younger migrants.

A 2021 working paper from the IMF, titled “The Impact of International Migration on Inclusive Development,” outlines some of the long-term benefits of welcoming immigrants.

“International migration is both a challenge and an opportunity for destination countries,” wrote its authors.

“On the one hand, especially in the short term, immigrants can create challenges in local labor markets, potentially affecting wages and displacing some of the native workers who compete with them. Their arrival may be a short-term one. Could also incur fiscal costs.”

However, the report noted that “particularly in the medium and long term, immigrants can boost production, create new opportunities for local firms and native workers, supplying the capacities and skills needed for growth.” can generate new ideas, stimulate international trade and contribute to the long-term fiscal balance by making the age distribution of advanced countries more balanced.”

Yet there is still a widespread belief in many European countries that new arrivals take in more than they contribute. In fact, the migrants receive little assistance from the state, forcing them to work hard to improve their conditions.

“EU policies have made it difficult for immigrants and refugees to stick labels on them. But that has not stopped them,” Dukhan said.

A child is rescued by members of the Spanish NGO Maydeteranio aboard the Eta Mari rescue boat while rescuing about 90 migrants in the Mediterranean open sea off the coast of Libya. (AFP)

“Those who are arriving have work experience, degrees and were important members of their former communities, and they want to do the same in their new homes. Although their degrees may not make sense in the new country, But many people will not sit idly by. They will get up, read, do strange things and do more.”

Despite the potential benefits of immigration, many Europeans remain troubled by the influx of foreigners. Through his exhibition, Dukhan hopes to challenge myths and misconceptions about migrants and refugees and show them in a more honest light.

“They are not unhappy people,” Dukhan said. “The media has played a major role in portraying them and placing them in a bubble to downgrade, scrutinize and ridicule them in a social experiment.”

As Europe tightens its borders and anti-immigrant sentiment continues to gain support, it may be easier to reverse these entrenched perceptions.

,