LONDON: You can’t see it with the naked eye, but above your head, at the height at which the highest-flying passenger jets cruise, there is a delicate layer of naturally occurring gas that is the most dense on Earth. Protects all life from harmful effects. Ultraviolet radiation emitted by the Sun.

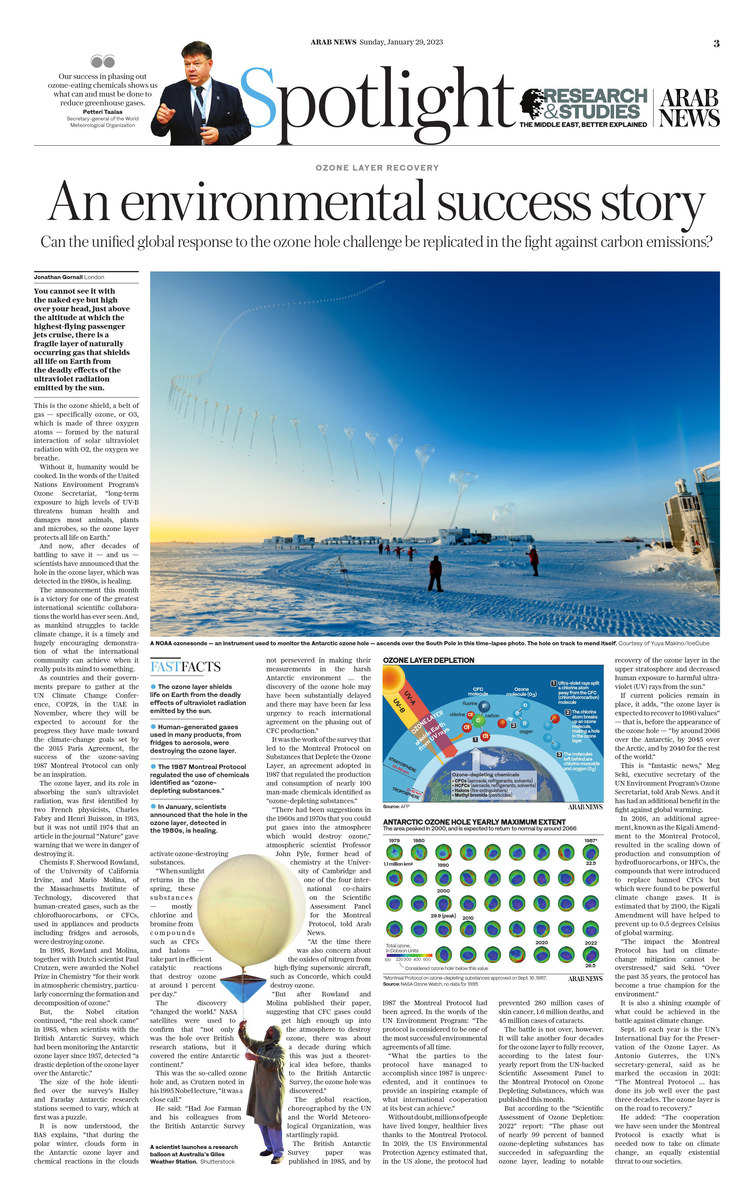

This is the ozone shield, a belt of gas – specifically ozone, or O3, which is made up of three oxygen atoms – formed by the natural interaction of solar ultraviolet radiation with O2, the oxygen we breathe.

Without it, we’d all cook. In the words of the Ozone Secretariat of the United Nations Environment Programme, “Prolonged exposure to high levels of UV-B threatens human health and harms most animals, plants and microbes, so the ozone layer protects all life on Earth.” does.”

But now, after decades of fighting to save it – and us – scientists have announced that the hole in the ozone layer, which was discovered in the 1980s, is on the mend.

This month’s announcement marks a triumph of one of the largest international scientific collaborations the world has ever seen. And, as the world struggles to deal with climate change, it is a timely and highly encouraging demonstration of what the international community can achieve when it really sets its mind to something.

As the world’s nations prepare to gather in the United Arab Emirates at the UN climate change conference, COP28, in November they are expected to give an account of progress made toward climate-change goals set by the 2015 Paris Agreement Will. The stupendous success of the ozone-saving 1987 Montreal Protocol can only be an inspiration.

The ozone layer, and its role in absorbing the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation, was first identified in 1913 by two French physicists, Charles Fabry and Henri Buisson, but it was not until 1974, in an article in the journal Nature. Nature Warned that we were in danger of destroying it.

University of California Irvine chemist F. Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that man-made gases, such as chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, are used in appliances and products such as fridges and aerosols. were destroying the ozone.

In 1995, Rolland and Molina, along with the Dutch scientist Paul Crutzen, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for their work in atmospheric chemistry, especially relating to the formation and decomposition of ozone”.

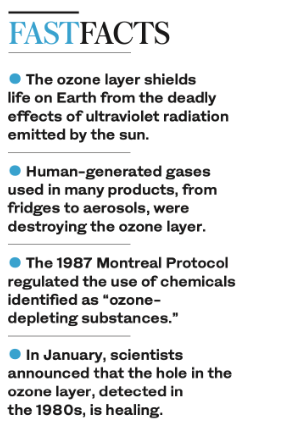

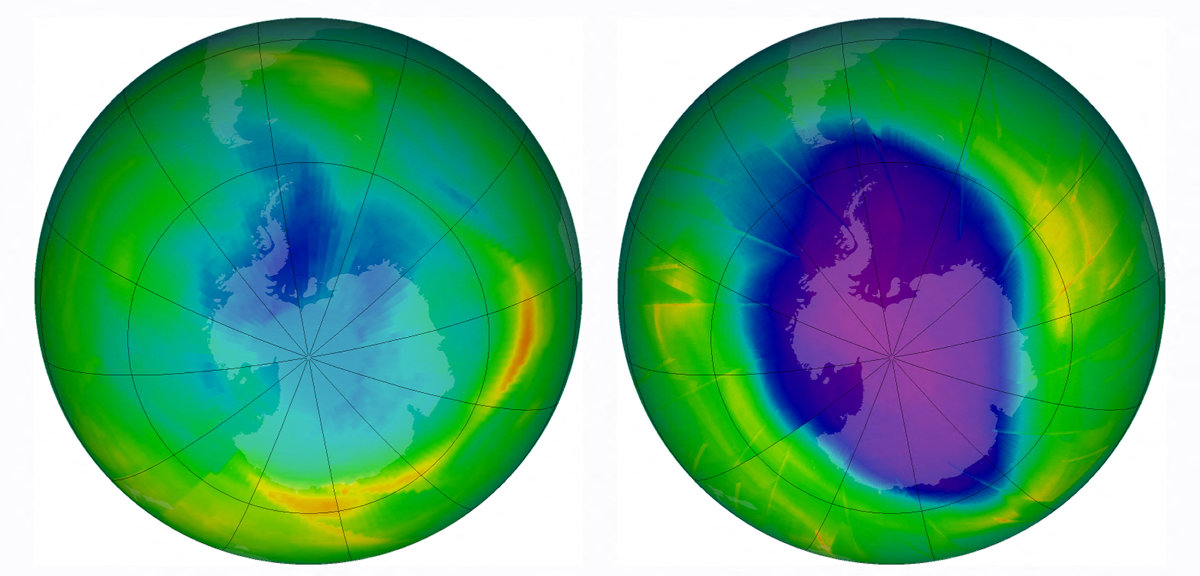

But, the Nobel quote continued, “the real shock” came in 1985, when scientists from the British Antarctic Survey, which had been monitoring the Antarctic ozone layer since 1957, detected a “massive depletion of the ozone layer over Antarctica”.

But, the Nobel quote continued, “the real shock” came in 1985, when scientists from the British Antarctic Survey, which had been monitoring the Antarctic ozone layer since 1957, detected a “massive depletion of the ozone layer over Antarctica”.

The size of the holes identified at the survey’s Halley and Faraday Antarctic research stations seemed to vary, which had previously been a puzzle.

It is now understood, explains Baas, “that during the polar winter, clouds form in the Antarctic ozone layer and chemical reactions in the clouds activate ozone-destroying substances.

“When sunlight returns in the spring, these substances — mostly chlorine and bromine from compounds such as CFCs and halons — take part in efficient catalytic reactions that destroy about 1 percent of ozone per day.”

The discovery “changed the world.” NASA satellites were used to confirm that “not only was the hole over British research stations, but it covered the entire Antarctic continent.”

This was the so-called “ozone hole” and, as Crutzen wrote in his 1995 Nobel lecture, “it was a close call.”

He added: “Had the British Antarctic Survey not determined that Farman and his colleagues had made their measurements in the harsh Antarctic environment … the discovery of the ozone hole could have been significantly delayed and had little urgency to reach international agreement.” could have been achieved by phasing out CFC production.”

It was the survey’s work that led to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, an agreement adopted in 1987 that identified the production and consumption of nearly 100 man-made chemicals as “ozone-depleting substances”. .

“There were suggestions in the 1960s and 1970s that you could put gases into the atmosphere that would destroy ozone,” said atmospheric scientist Professor John Pyle, former head of chemistry at the University of Cambridge and one of four international co-chairs Huh. the Scientific Evaluation Panel for the Montreal Protocol told Arab News.

“At the time there was also concern about oxides of nitrogen from high-flying supersonic aircraft like the Concorde, which could destroy ozone.

“But after Rowland and Molina published their paper, suggesting that CFC gases could rise high enough in the atmosphere to destroy ozone, nearly a decade ago it was just a theoretical idea, the British Antarctic Survey, Thanks to the hole was discovered.

The global response, choreographed by the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization, was almost astonishingly swift.

The British Antarctic Survey paper was published in 1985 and by 1987 the Montreal Protocol had been agreed upon. In the words of the United Nations Environment Programme: “The Protocol is considered one of the most successful environmental agreements ever.

“What the parties to the Protocol have managed to achieve since 1987 is unprecedented, and provides an inspiring example of what international cooperation at its best can achieve.”

Without a doubt, millions of people have lived longer, healthier lives thanks to the Montreal Protocol. In 2019, the US Environmental Protection Agency estimated that the protocol had prevented 280 million cases of skin cancer, 1.6 million deaths, and 45 million cases of cataracts in the US alone.

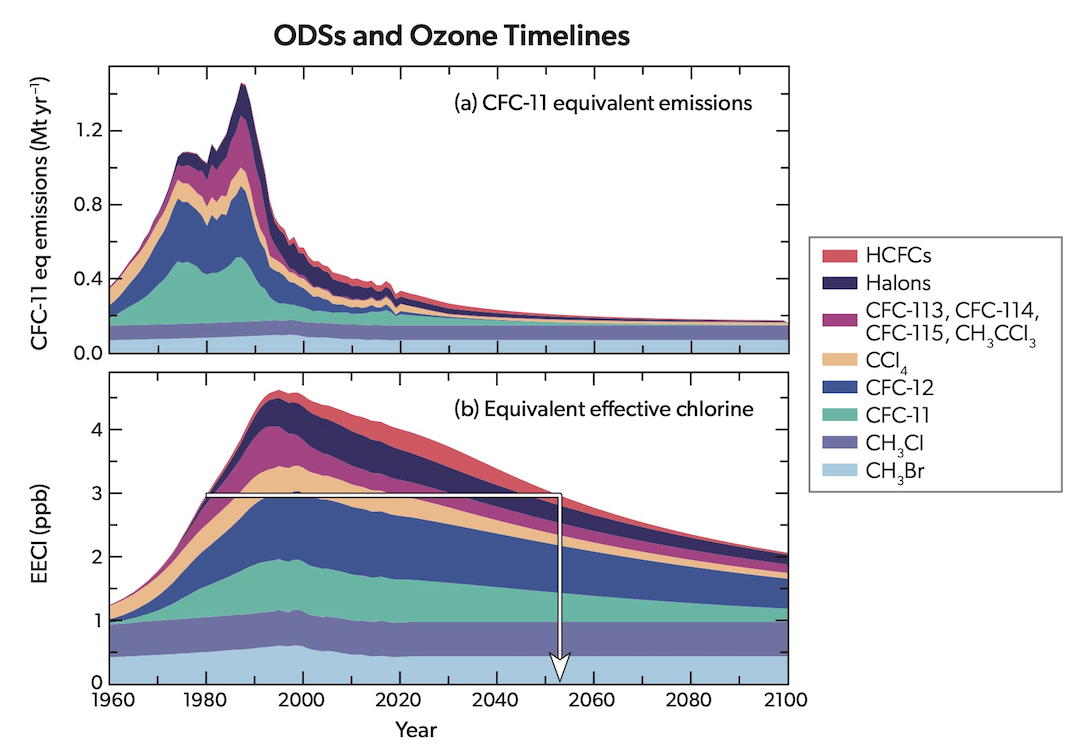

However the fight is not over. It will take another four decades for the ozone layer to fully recover, according to the Montreal Protocol’s latest four-year report from the United Nations-backed Scientific Assessment Panel on Ozone Depleting Substances, published this month.

But according to the “Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022” report: “The phase-out of about 99 percent of the banned ozone-depleting substances has been successful in protecting the ozone layer, leading to a significant recovery of the ozone layer in the upper stratosphere and reducing human exposure to harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays from the sun.”

If current policies persist, it said, “the ozone layer is expected to recover to 1980 values”—that is, before the ozone hole appeared—”over the Antarctic by about 2066, over the Arctic by 2045, and by 2040 for the rest of the world.

This is “fantastic news”, Meg Seki, executive secretary of the UN Environment Programme’s ozone secretariat, told Arab News. And it has an added advantage in the fight against global warming.

In 2016, an additional agreement, known as the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, resulted in reductions in the production and consumption of hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, compounds that were introduced to replace banned CFCs but which have been found to be potent climate changers. Had gone. Gases. It is estimated that by 2100, the Kigali Amendment will have helped to limit global warming to 0.5 °C.

“The impact of the Montreal Protocol on climate change mitigation cannot be overstated,” Seki said. “Over the last 35 years, Protocol has become a true champion for the environment.”

It is also a shining example of what can be achieved in the fight against climate change.

Every year 16 September is the United Nations International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer. Marking the occasion in 2021, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said: “The Montreal Protocol… has done its job well over the past three decades. The ozone layer is on its way to recovery.”

He added: “The co-operation we have seen under the Montreal Protocol is really needed to tackle climate change, an equally existential threat to our societies.”